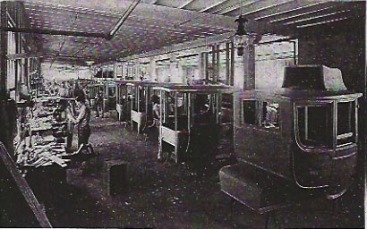

The Detroit Electric Machining Room circa 1910

(From Chapter One)

The first part of the body I saw was half of the left arm. It hung off the side of the hydraulic roof press, hazy in the dim yellow light of the gas lamps. I walked farther into the machining room, cutting through shadows of pulleys and concrete pillars. Odd flecks of matter on other machines sparkled as I moved. The factory was silent other than a slow drip, like a leaking faucet.

Closer now—a black coat sleeve dangled from the steel plates of the press, pinched just below the elbow. A bright crimson cuff encircled a red wrist. A red hand sagged, palm out, five dark droplets stretching from the ends of red fingers, then letting go one after another and plunging into the pool two feet below. The room smelled of a butcher shop—viscera and blood.

I crept past the drilling machines and looked down the aisle. The lower half of a large man hung from the front of the press, trousers shiny black above dark-stained stockings and garters. His black button-top shoes, heels pressed against the machine, leaked still more droplets into the dark pool only a few inches below them. The body was upright and complete to the waist. It ended there, where the upper and lower plates of the press met, as if the rest of the man had simply disappeared.

The first part of the body I saw was half of the left arm. It hung off the side of the hydraulic roof press, hazy in the dim yellow light of the gas lamps. I walked farther into the machining room, cutting through shadows of pulleys and concrete pillars. Odd flecks of matter on other machines sparkled as I moved. The factory was silent other than a slow drip, like a leaking faucet.

Closer now—a black coat sleeve dangled from the steel plates of the press, pinched just below the elbow. A bright crimson cuff encircled a red wrist. A red hand sagged, palm out, five dark droplets stretching from the ends of red fingers, then letting go one after another and plunging into the pool two feet below. The room smelled of a butcher shop—viscera and blood.

I crept past the drilling machines and looked down the aisle. The lower half of a large man hung from the front of the press, trousers shiny black above dark-stained stockings and garters. His black button-top shoes, heels pressed against the machine, leaked still more droplets into the dark pool only a few inches below them. The body was upright and complete to the waist. It ended there, where the upper and lower plates of the press met, as if the rest of the man had simply disappeared.

The Detroit Electric Body Department circa 1910

(From Chapter Two)

A policeman, in a dark uniform and tall bobby hat, stood with his arms crossed in the doorway, silhouetted by the factory lights behind him. He must have recognized Wilkinson, because he didn’t say anything, just stood aside and waved us by.

Once we were past the policeman’s range of hearing, Wilkinson said, “What did you do to your leg?”

“Fell off a curb and twisted my ankle. I wasn’t paying attention.”

He glanced at me, frowning, before continuing on toward the back of the factory. “You seem to not be paying attention to a number of things.”

The shadows cast by the gas lamps brought back the grisly image of Cooper’s body. My heart pounded. The echoes of our footsteps surrounded us as we passed through the paint department, then the large body shop and its huge woodworking machines. Unfinished automobile bodies, like stripped wooden carcasses, littered the floor. Next came electrical, then the trim department and its stacks of untreated cow and goat hide, their rotten flesh stench making me breathe through my mouth. Finally, about two-thirds of the way back, my department—machining—where, other than the motors, which were made at our plant in Cleveland, all our automobile parts were finished, including the seamless aluminum roofs stamped out by one of the largest hydraulic presses in Detroit.

A policeman, in a dark uniform and tall bobby hat, stood with his arms crossed in the doorway, silhouetted by the factory lights behind him. He must have recognized Wilkinson, because he didn’t say anything, just stood aside and waved us by.

Once we were past the policeman’s range of hearing, Wilkinson said, “What did you do to your leg?”

“Fell off a curb and twisted my ankle. I wasn’t paying attention.”

He glanced at me, frowning, before continuing on toward the back of the factory. “You seem to not be paying attention to a number of things.”

The shadows cast by the gas lamps brought back the grisly image of Cooper’s body. My heart pounded. The echoes of our footsteps surrounded us as we passed through the paint department, then the large body shop and its huge woodworking machines. Unfinished automobile bodies, like stripped wooden carcasses, littered the floor. Next came electrical, then the trim department and its stacks of untreated cow and goat hide, their rotten flesh stench making me breathe through my mouth. Finally, about two-thirds of the way back, my department—machining—where, other than the motors, which were made at our plant in Cleveland, all our automobile parts were finished, including the seamless aluminum roofs stamped out by one of the largest hydraulic presses in Detroit.

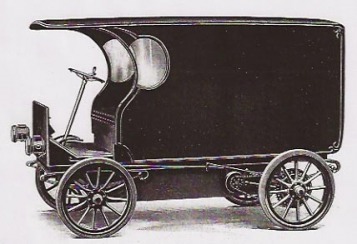

1911 Detroit Electric Model 601, Panel Body

(From Chapter Twenty-Seven)

Ben Carr looked through the window. He hesitated before opening the door, probably remembering what had happened the last time I showed up here at night. “We’ve got the 601 ready to go,” he said, not quite meeting my eyes. He gestured vaguely over his shoulder at the boxy black truck, which stood in front of the closed garage door. The electric lights in the room were bright, sparkling off the shiny finishes of the automobiles arrayed around the outside walls. I was taken, as I always was, by the fresh-air ozone scent of the building.

I extended my hand to him, and he took it. “I’m so sorry, Ben,” I said. “No matter what happens to me, it was wrong to get you involved in this mess.”

His face relaxed a little. “Thank you, sir. I’m sorry I couldn’t help you, but I . . . I just couldn’t.”

“I understand. I can’t tell you how relieved I was when Detective Riordan said he wasn’t pressing charges against you.”

Ben looked at his feet. “You know I got to testify.”

“Of course you do. But don’t worry. I’m going to get out of this,” I said, with a great deal more confidence than I felt.

His eyes darted to mine and then away again. “I left the logbook on the front seat of the truck. Don’t forget to fill it out.”

“Sure, thanks.”

He began to turn around, hesitated, then spun and marched toward the back of the garage. “Just leave it on that stool by the tool crib,” he called over his shoulder. “I’ll get it later.”

I watched him until he turned the corner into the office. He wanted my handwriting in the logbook. I couldn’t blame him. I walked over to the truck, wrote the details in the book, and set it atop the stool.

The truck was nothing fancy, just a twelve-foot-long box with a cutout in the front for a bench seat over the white Motz cushion tires. The only thing in front of the driver other than the steering wheel—which I thought awkward in comparison to the steering lever on our automobiles—was a one-inch wood panel that held the headlights.

I walked around to the back and swung the doors open. A tool kit and spare tire were inside, but nothing else. There was plenty of room for a body—for a number of bodies. With its one-ton capacity, I reckoned I could get eight or nine more Judge Hume-sized corpses inside without taxing the suspension or motor. And the way my life was going, that could come in handy.

After I opened the garage door, I climbed in the truck and checked the amp and volt meters. The batteries were fully charged. That gave me a range of at least fifty miles—much more than I needed.

Ben Carr looked through the window. He hesitated before opening the door, probably remembering what had happened the last time I showed up here at night. “We’ve got the 601 ready to go,” he said, not quite meeting my eyes. He gestured vaguely over his shoulder at the boxy black truck, which stood in front of the closed garage door. The electric lights in the room were bright, sparkling off the shiny finishes of the automobiles arrayed around the outside walls. I was taken, as I always was, by the fresh-air ozone scent of the building.

I extended my hand to him, and he took it. “I’m so sorry, Ben,” I said. “No matter what happens to me, it was wrong to get you involved in this mess.”

His face relaxed a little. “Thank you, sir. I’m sorry I couldn’t help you, but I . . . I just couldn’t.”

“I understand. I can’t tell you how relieved I was when Detective Riordan said he wasn’t pressing charges against you.”

Ben looked at his feet. “You know I got to testify.”

“Of course you do. But don’t worry. I’m going to get out of this,” I said, with a great deal more confidence than I felt.

His eyes darted to mine and then away again. “I left the logbook on the front seat of the truck. Don’t forget to fill it out.”

“Sure, thanks.”

He began to turn around, hesitated, then spun and marched toward the back of the garage. “Just leave it on that stool by the tool crib,” he called over his shoulder. “I’ll get it later.”

I watched him until he turned the corner into the office. He wanted my handwriting in the logbook. I couldn’t blame him. I walked over to the truck, wrote the details in the book, and set it atop the stool.

The truck was nothing fancy, just a twelve-foot-long box with a cutout in the front for a bench seat over the white Motz cushion tires. The only thing in front of the driver other than the steering wheel—which I thought awkward in comparison to the steering lever on our automobiles—was a one-inch wood panel that held the headlights.

I walked around to the back and swung the doors open. A tool kit and spare tire were inside, but nothing else. There was plenty of room for a body—for a number of bodies. With its one-ton capacity, I reckoned I could get eight or nine more Judge Hume-sized corpses inside without taxing the suspension or motor. And the way my life was going, that could come in handy.

After I opened the garage door, I climbed in the truck and checked the amp and volt meters. The batteries were fully charged. That gave me a range of at least fifty miles—much more than I needed.

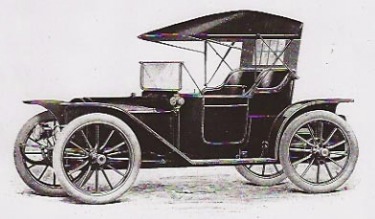

1911 Detroit Electric Model 17 Underslung Roadster

(From Chapter Twenty-Eight)

The most important car we would be showing was the Model 17 underslung roadster ($2,000 with standard lead batteries). It was a rakish beauty half a foot closer to the ground than anything we’d previously made, with a long “engine compartment” (actually a trunk) in front. It sat gleaming, deep blue body over straw-colored chassis, in the front of the garage.

The market was evolving at a glacial pace. More cars at the show this year would be enclosed coupés and broughams, but the majority were still roadsters—open-topped touring cars poorly suited for cold weather driving, but well suited for the average man’s image of himself as a rough and tumble sportsman. The Model 17 was our attempt to break into that market. If Detroit Electric was to succeed in the long term, we had to make automobiles that were considered “manly.”

The most important car we would be showing was the Model 17 underslung roadster ($2,000 with standard lead batteries). It was a rakish beauty half a foot closer to the ground than anything we’d previously made, with a long “engine compartment” (actually a trunk) in front. It sat gleaming, deep blue body over straw-colored chassis, in the front of the garage.

The market was evolving at a glacial pace. More cars at the show this year would be enclosed coupés and broughams, but the majority were still roadsters—open-topped touring cars poorly suited for cold weather driving, but well suited for the average man’s image of himself as a rough and tumble sportsman. The Model 17 was our attempt to break into that market. If Detroit Electric was to succeed in the long term, we had to make automobiles that were considered “manly.”