|

Choosing a compelling setting for a historical can be challenging, particularly for a series. An author has to be sure the setting is enough to carry more than a single book. Each new book must illuminate new events, people, or places. (And given that most publishers want a series to remain pretty stationary in terms of locale, that means new places within the overall setting.)

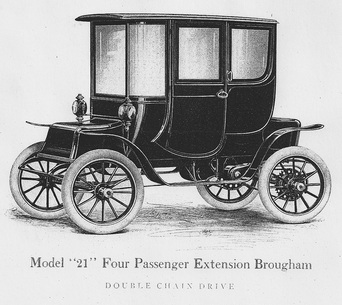

I should note that not all historicals use events the way I do. I suppose it’s the teacher in me that wants to illuminate a bit of history along with an entertaining story, but many historicals are more about the feel of the era, rather than the events. As for me, here’s how it worked: When I started researching The Detroit Electric Scheme, I was pretty sure I wanted to use the early automotive industry as the major backdrop for the book, but as I came across more and more information on the early electric car, I decided to focus the story there. My protagonist became Will Anderson, the son of William C. Anderson, the real president of Detroit Electric, America’s most successful early electric car company. DE made electric cars from 1907 to 1939 and became the number one manufacturer of electrics in 1910. I discovered that the tipping point from success to eventual failure for electrics came in early 1911, so I set the book to end at that point. I also looked for mileposts to use in future books. Fortunately, Detroit has a colorful history that provided me with lots of options. (Back to my point about publishers and locales—I wanted Will to chase the antagonist of the second book to Panama, where the building of the canal would serve as Backdrop II. St. Martin’s Press wanted Will to stay in Detroit, so that book never got written.) Book two, Motor City Shakedown, was originally planned as the third book in the series, and takes Will through the first mob war in Detroit history, a real bloodbath between the Adamo and Gianolla gangs. I kept my eyes and ears open while I was writing those two, looking for a compelling setting within the Detroit of 1912. I kept hearing about this place called Eloise Hospital, which served, among other things, as the Detroit area’s insane asylum for nearly a century and a half. Every other person I talked to around Detroit had some memory of Eloise—usually a relative they had to visit. The memories were uniformly frightening to the individual, with the exception of one man who fondly remembered Sunday picnics on the lawn. (He didn’t have a relative on the inside.) Eloise became the setting for a significant part of Detroit Breakdown, which focuses on mental health treatment a hundred years ago. This was a tipping point from containment to treatment, as psychoanalysis started to come into its own. Eloise Hospital stretched over 900+ acres, with seventy-five buildings and over 10,000 patients and inmates at one time! It was a city unto itself, with farms, bakeries, canneries, sixteen kitchens, a fire department, police department, and a cemetery (which today holds over 7,000 graves, none of which are marked other than with a number, and no index or map has survived). Now I just had to figure out how to get Will inside Eloise. (It wasn’t too challenging, given his lack of stability.) When I finished that book, my options were feeling limited. There was the massive salt mine under the city, which I thought would be interesting, but not enough to carry a book. I could go back to the underworld, but I felt I got enough of that in the second book. Then I realized I had never taken a good look at Detroit politics of the day, and I hit on two major scandals. In the summer of 1912, all but one Detroit aldermen were caught in a bribery sting, elaborately planned and carried out by the detective agency of William Burns, known at the time as “America’s Sherlock Holmes.” At the same time, campaigning was in full swing for the presidential election as well as for a amendment to the Michigan constitution to allow women the vote. (Can you imagine it? Women voting? Many—including many women—couldn’t.) The election was peppered with the kind of voter fraud that can only be found in the Third World these days, and in the end the amendment was defeated. Michigan women had to wait seven more years before they could vote. As I had set up Will’s on-again, off-again girlfriend, Elizabeth Hume, as a suffragist, I was able to fit them into this story as well. So, four books covering the rise and fall of the early electric, Detroit’s first mob war, a huge insane asylum, and political corruption, all taking place between 1910 and 1912. All events and/or places I find compelling. “Now what?” you may ask. The answer—a book set in Chicago.

0 Comments

Detroit has been hung with a few nicknames over the years, but it’s probably been a few years since you heard it called the “Paris of the West.” Okay, I know. You’ve never heard it called that. But in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century, before “Motown,” “Motor City,” and more recently, “Murder City,” people called Detroit the “Paris of the West.”

And it was for good reason. It was a beautiful city, full of green space, culture, and stunning architecture. Detroit’s streets were originally laid out by Augustus Woodward in a spoked-wheel design, emulating Washington D.C. The city was filled with parks and wide boulevards. Some of the earliest skyscrapers in the United States were built here around the turn of the century. (At the time, the term “skyscraper” meant a building of ten stories, give or take.) The city had a well-funded and-attended opera, symphony, ballet, and art museum. On top of that, commerce boomed. Detroit became one of the great hubs of manufacturing in the country, leading or being one of the leaders in stoves, cigars, train cars, and a myriad of other items. The city’s location was perfect—ever since the Erie Canal opened in 1825, the Detroit River connected the Great Lakes to New York and the Atlantic. Natural resources were plentiful. Most of Michigan was forest, and its Upper Peninsula was one of the great mining regions of the world. All of this makes for a nice place to live, but it’s a very incomplete picture of Detroit in the early Twentieth Century, which is when my novels are set. Nice places to live are fine and dandy, but not the greatest places to set dark mysteries. Fortunately (for me), the time period and city were layered with much more interesting people and problems. Every city has its “dark underbelly,” and we all expect Detroit’s to be extra dark. You wouldn’t be disappointed. One reason manufacturing was so strong was the Employers Association of Detroit, which acted as a sort of outsourced human resources company for the city’s manufacturers. The EAD specialized in keeping out unions, thereby controlling wages. They planted spies in factories, beat up agitators, and even brought in muscle from organized crime when necessary. Speaking of crime, the newspapers estimated there to be more than 1,000 street gangs in the city in 1910. Sicilian gangs had begun the takeover of the city’s rackets. Illegal importing was a huge moneymaker, because import duties were so high at the time, often doubling the price of an imported item. The Detroit River made a convenient smugglers’ highway, with Canada less than half a mile away from the city. And I can’t write about Detroit crime without including city government. In July 1912, twenty-six of Detroit’s thirty-six aldermen were arrested for bribe-taking, and in true Detroit fashion, by the end of 1914, every one of them had either been acquitted or had the charges dropped. This in spite of the prosecution’s open-and-shut cases against many of them, including audio recordings of the men demanding bribes in one of the earliest uses of wiretapping. Detroit’s people were fascinating. According to the 1910 census, less than 10% of Detroit’s 465,000 residents were even born in the State of Michigan. The rest came over in great waves of emigration, first from Western Europe, primarily Germany and Ireland, and then, in the early Twentieth Century, from Southern and Eastern Europe. The city was a patchwork of ethnic enclaves, like a smaller version of New York City. Most of those people lived in squalor. It was a great time to be alive if you had money, but for the other 99.99%, live was hard—no government social programs like unemployment insurance or welfare, dollar-a-day wages that didn’t feed a family, and crumbling tenements in which to live. The masses from Europe came for the opportunity, and for most the reality didn’t live up to the dream. This mash-up of rich and poor, grand success and sweeping failure, honesty and vice makes for a perfect crucible for stories of people’s experiences, good and bad, with most, like our own personal stories, usually somewhere in between. |

AuthorD.E. Johnson: Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed