by D.E. Johnson Detroit has been overshadowed by New York and Chicago when it comes to organized crime, but it has plenty of history of its own. One of the reasons I chose the time period I did for my series (1910 – 1913) was that it coincided with the city’s first mob war. Vito Adamo was a Sicilian immigrant who came to America around 1900. He was a grocer in a little town called Ford City, which is now a part of Wyandotte, in the general area described by most Detroiters as “downriver.” He was, of course, more than a grocer, but I mention it because he had some competition across the street—the Gianolla brothers, who opened a grocery a few years after he did. Vito and his brother, Salvatore, had systematically gained control over the Sicilian and Italian crime of the time, both in Ford City, which had a large Italian population, and in Detroit’s Little Italy. That crime included the Black Hand (the protection racket), illegal immigration (Canada is right across the river from the city), importation of duty-free goods (the U.S. was very protectionist at the time, and duties could as much as double the sale prices of foreign goods), and, of course, the “numbers,” or Italian lottery. It was beer sales, however, that started things with the Gianollas. The Adamos had a stranglehold on beer sales in the area they controlled, which was virtually all the territory available to a Sicilian gang at the time. Tony Gianolla saw opportunity and went to the Adamo’s customers with a significant cut in beer prices. When faced with the lost business, Vito Adamo decided to match the prices and throw in ice, a necessity at the time. The Gianollas took umbrage at this and beat up a few delivery drivers. This led to retaliation by the Adamos and, finally, to a shotgun war on the streets of Detroit. Prior to this, the Adamos were unknown to the Detroit police, and the Gianollas had only recently become suspects in the gruesome murder of a former associate. The Ford City police had raided the Gianolla’s store and confiscated about $2,000 in illegal olive oil. ($2,000 was about a year-and-a-half’s wages for a laborer in 1913—a lot of money.) Tony Gianolla suspected a man named Sam Buendo of ratting them out to the police. Buendo’s mutilated and burned body was found shortly thereafter in a nearby field. As the war between the gangs ramped up, the police were still unclear as to the identity of the factions. The close-range shotgun executions, which was really what these murders amounted to, occurred throughout 1913, and were plastered across the front page of the Detroit newspapers for the better part of a year. Both sides lost soldiers until November, when members of the Gianolla gang caught Vito and Salvatore Adamo unawares and gunned them down. The remaining members of the Adamo gang scattered to the wind, and the Gianollas became the bosses—until they were brutally murdered six years later by an associate named John Vitale, who was next in line to run things. An interesting side note is that after Vito Adamo was killed, the police searched his home and found a notebook with pages full of Italian writing and drawings of murder scenes, such as stilettos plunging into men’s backs. The newspapers reported that this might be the break the police had been looking for—a detailed description of the events of the war as well as the players involved. When they had it translated, they found that Vito Adamo was an aspiring author. The notebook was his attempt at a dime novel and was the story of a poor Sicilian boy who resorted to murder only as revenge when persecuted beyond all reason. Perhaps Vito Adamo felt that he was that boy. History remembers him differently.

6 Comments

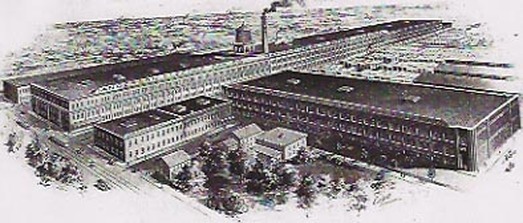

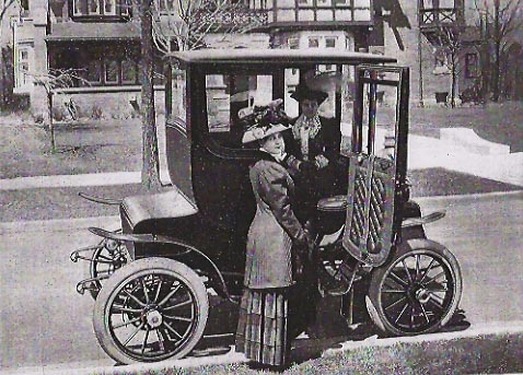

Detroit Electric Factory, Clay Avenue, Detroit, 1911 Detroit Electric Factory, Clay Avenue, Detroit, 1911 (Reprinted from Michigan History Magazine) Are electric cars in Detroit a new concept? Not hardly. The first such vehicles debuted on the streets of the Motor City more than 100 years ago. With names like Century, Detroit Electric, Flanders, Grinnell, and Hupp-Yeats, these no-crank automobiles (and some trucks) appealed to doctors and delivery men because of their quick and easy startups. Women were another strong customer category; the absence of the crank as well as a lack of noise and noxious fumes were viewed as very appealing features to the distaff side. Detroit dominated the gasoline-powered automobile business in the early 1900s, but many people don’t know about the city’s simultaneous foray into electrics, which included the most successful electric car company in U.S. history. The manufacturers of electrics had a heady 20 years or so during which their possibilities looked endless. But a number of factors combined to seal their fate, and they had all but disappeared from the Michigan landscape by the end of World War I. The first electric car was built in Scotland in 1837, although it wasn’t until 1896 that the first American-made production electrics were offered by the Pope Manufacturing Company of Boston, Massachusetts and the American Electric Vehicle Company (later Waverly Electric) of Chicago, Illinois. By the turn of the century, 38 percent of all the automobiles on American roads were electrics. (Forty percent were steam-powered and the remaining 22 percent used gasoline.) The first car to go more than a mile a minute was an electric, as were the winners of the first track race and the first hill-climbing contest. In 1900, there were 75 electric car companies in the U.S. (although many folded before producing anything more than a prototype). By the end of the decade, that number had been whittled down to 46, almost all of them different from the ones that existed 10 years earlier. Every month, more came in and just as quickly went out. Targeted Marketing By 1910, electric cars were marketed toward three distinct customers: rich women, city doctors, and urban delivery companies. For doctors and delivery companies, the benefit was obvious. They made frequent stops throughout their day, and using the manual “crank” starter on a gasoline-powered vehicle was inconvenient and sometimes dangerous. (Some people were even killed when the engine kicked back and the crank spun unexpectedly.) Further, electrics had plenty of range—50 to 100 miles per charge, depending on the model—to cover the necessary distances without worry. Women were also concerned about the starter. The process of bending down, grabbing hold of the crank, and giving it a spin was considered unladylike. Women who drove were already at the edge of what might be considered socially acceptable, and that additional bit of manual labor was too much for many modern women to stomach. The price of batteries (of the lead-acid variety, as you would find today) drove the cost of electric cars to exceed the price of comparable gas automobiles by at least 50 percent. But the ease of starting, combined with the lack of noise and noxious fumes, earned a place for the electric in American society. Detroit’s Contributions At least half a dozen electric car companies were formed in Detroit in the early 20th century: Century, Columbian, Detroit Electric, Flanders, Grinnell, and Hupp-Yeats. Columbian was short-lived and produced only a handful of automobiles, but the other manufacturers each had some measure of success. All of these companies advertised a range of up to 100 miles on a charge—more than enough distance in an era of 10-mile-per-hour speed limits and barely passable rural roads. The primary market for electric cars after 1910 was at the high end, with models priced at $2,500 and up. Given this, some companies thought they saw an opportunity for a less expensive automobile to succeed. One such company was Century Electric, which operated from 1912 to 1915. Century made lighter-weight cars with a long, underslung chassis that was hung below the axles rather than set atop them. This last feature lowered the vehicle’s center of gravity, making it safer to round tight corners at high speeds. Century manufactured open-body roadsters (available at only $1,250 in 1912) as well as enclosed broughams, which looked similar to opera coaches. These days, Century is little more than an asterisk in the history of the electric car. Flanders Electric debuted in 1912 and was the brainchild of Walter Flanders, Henry Ford’s former production manager and the “F” in the E-M-F automobile company. The Pontiac auto maker was successful in the gasoline-car market with its “Flanders 6,” but saw an opportunity to build electrics as well. It made plans to take over the market, pricing its electrics from $1,775 to $2,500. The Flanders’ look was notable for the absence of a hood; the company’s brochures even ridiculed electric car companies that chose to add that needless feature. Electric-car motors were placed under the automobile—or, in the case of Flanders’ cars, in the back because they were built low to the ground—so there was no need for a traditional hood, other than for aesthetic reasons. It’s said that Flanders spent the better part of a million dollars promoting its product line. After producing fewer than 100 electric cars and finding itself in receivership, Flanders entered the history books in 1914. The Grinnell Electric Car Company was owned by the same family as the Grinnell Brothers Piano Company. Grinnell’s automobiles, manufactured from 1913 to 1914, were reminiscent of the products of industry leaders such as Baker—a prominent Ohio brand—both in design and in customer focus. The company aimed at the high-end market, and primarily built enclosed-body coupes and broughams that ranged from $2,800 to $3,400. Grinnell did little to differentiate itself from its competitors, though, and soon found its cars on the scrap heap. Hupp-Yeats Electric was one of the more successful electric car companies of the era. The company was founded by Robert Hupp of Hupmobile fame and was in business from 1911 to 1919. Hupp worked for Ford and Oldsmobile prior to founding Hupmobile with his brother, Louis. After disagreements with the company’s financial backers, Robert left the business in 1910 to start the RCH Company, later changed to Hupp-Yeats Electric. Hupp-Yeats automobiles had stylish sloping hoods, curved roofs, and underslung bodies, and were available as coupes or runabouts. In 1911, they were priced from $1,650 to $2,150 and delivered as much as 125 miles on a charge. The brand most closely associated with Detroit and electric cars is Detroit Electric, for many more reasons than the name. The firm was originally named the Anderson Carriage Company, and moved from Port Huron to Detroit in 1895 in order to take advantage of the larger market. Anderson’s was a big carriage works, making everything from inexpensive utility wagons to beautiful opera coaches. The company put out its first automobile, the Detroit Electric Model A, in 1907. That year, it sold only 10 cars. In 1908, its first full year of manufacture, the public purchased 184 of its four models—a very respectable number, given the regional nature of business at the time and the still-small luxury automobile market. By 1910, Detroit Electric had become the best-selling brand of electrics in the country, delivering 797 automobiles and a small number of electric trucks. In the early 1910s, Detroit Electrics were priced at $2,000 for an underslung roadster to as much as $4,750 for a limousine with the Edison nickel-steel battery. (It’s worth noting that, during this time period, the average annual income was about $1,000.) Detroit Electric wasn’t a particularly innovative company. But William C. Anderson and his team, which included chief engineer George Bacon, had great business sense and understood their clientele very well. For rich women, Anderson’s team focused on luxury. Each of the Detroit Electric coupes and broughams came with a flower vase, a case for makeup and business cards with a built-in watch, and in some cases a “gentleman’s smoking kit.” The upholstery choices included “22 ounce superfine Waterloo broadcloth or leather, blue, green, or maroon shades. Imported goatskin, fancy novelty cloth or whipcord on order.” Standard exterior paint colors were blue, Brewster green, or maroon, although they would paint a car any color a customer chose for an additional fee. (In 1909, a Mr. Capewell bought Detroit Electric’s first stretch limousine in an eye-popping shade of canary yellow.) As new features came onto the market from other manufacturers, the management team at Anderson would evaluate them and incorporate the ones that made sense for their customers. Examples include emulating the direct-shaft drive of Baker electric cars—which ensured a quieter ride—as well as a “duplex drive” feature, which allowed the driver to sit either in the front seat or the back seat. (The Ohio Electric Car Company had introduced this idea a year before Detroit Electric.) Interestingly, enclosed automobiles of the day were designed much the same as the coaches that preceded them. Typically, a bench seat was fitted against the back wall of the automobile, allowing for two passengers to sit comfortably. In front of them was either another bench seat set against the front wall facing back, or a combination of a small bench seat set into the front left corner of the interior, facing diagonally toward the rear, and a flip-up “jump seat” on the right side, also facing back. The driver would sit in the left rear and have to look around passengers to see the road. This feature, nonsensical as it may seem, was the way horse-drawn coaches were designed, and it was what the luxury market expected. But as the streets became more crowded, accidents occurred on a more frequent basis. This forced municipalities to enact ordinances banning the use of rear-drive automobiles. The “Detroit Duplex Drive” feature allowed for the traditional layout with rear drive, but the left front seat also could be turned to the front to allow the driver to navigate from there. Detroit Electrics, like most enclosed cars of the day, used steering “tillers,” rather than steering wheels. The tiller could be placed against the side of the interior when not in use and was swung up by the driver when he or she was ready to go. Detroit Electric purchasers included Thomas Edison, Pierre DuPont, David Gamble, C.W. Post, Mrs. J.D. Rockefeller Jr., Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, Anna Kresge, Charles Steinmetz, Stanford White, and the Steinway family. Surprisingly, they were joined by the owners of several gasoline-automobile companies of the day, including Henry Ford—who bought two for his wife and one for his son—and the men who oversaw Packard, Stutz, Cadillac, E-M-F, Studebaker, and General Motors. It should be noted that the Ford Motor Company took a hard look at electrics, going as far as developing a number of designs in 1914. During this period, Henry Ford’s friend, Thomas Edison, had experienced some serious financial problems, and Ford thought he would help him by building cars that used the inventor’s batteries. Unfortunately, Ford’s designers were unable to create a car that fit within their boss’ pricing parameters—namely, they couldn’t build one nearly cheaply enough. Drawbacks The cost of electric cars, even at the low end, wasn’t the only thing holding most people back from making a purchase. Range was a concern, particularly as most rural areas were not yet wired for electricity. It was easy to transport gasoline out into the country, less so electricity, so drivers of electrics—for the most part—had to stay close to home. Compounding the problem, the batteries needed half a day to charge, so there was no short stop to “refuel” before getting on the road again. The biggest problem, however, was the electric car’s identification with women. In the early 1900s, “manliness” wasn’t something most men would compromise, so the idea of driving a “woman’s car” was unthinkable. The electric car manufacturers tried to entice men with low-slung, racy-looking roadsters, but were unsuccessful at breaking out of the stereotype. Ultimately, the self-starter developed by Charles Kettering in 1911 spelled the end of the early electric. Kettering’s starter allowed drivers of gasoline automobiles to start their cars without a crank, which made them acceptable to most female drivers. The Fall With all of these factors working against the electrics, the market for such cars continued to shrink until the late 1910s, by which time most manufacturers had gone under. Detroit Electric, however, remained in business until 1939, but not without some effort. At its high point, the company manufactured almost 2,000 vehicles a year. Through the 1920s, its annual output dropped to the low hundreds. Then, the stock market crash of 1929 put it into bankruptcy. Its assets were purchased and the new company struggled along for another decade, manufacturing a handful of cars each year from a combination of new and old parts and staying in business only because of the service work they performed. By 1939, there wasn’t enough of that to keep the company afloat, and it quietly folded. All told, Detroit Electric built nearly 14,000 electric vehicles—the most of any U.S. manufacturer. In the wake of the demise of the early electric, one can’t help but wonder how Flanders Electric might have reconsidered this statement from their 1912 sales brochure: “Is there a rule to guide one? There is. And it is a very simple one. If an innovation is logical it will survive. It will become permanent. On the other hand—if it is one of those so called improvements devised by [hare]-brained designers simply to create a selling argument or a talking point; if, in short, it is but the hobby of an individual it will become a fad of the moment and as fads do will soon pass into oblivion.” D.E. Johnson is the award-winning author of the Will Anderson Historical Detroit mystery series. Those books include The Detroit Electric Scheme, Motor City Shakedown, Detroit Breakdown, and Detroit Shuffle. Thanks to the Motor Cities National Heritage Area for their assistance with this story. SIDEBAR: A GLOSSARY OF EARLY CAR BODY TERMS In 1916, the Nomenclature Division of the Society of Automobile Engineers established formal definitions for the many styles of car bodies then on the road. Among the entries listed were: Roadster— An open-body automobile seating two or three persons. It may have additional seats on the running boards or in a tonneau (rumble seat). Runabout—Editor’s note: This is often a synonym for “roadster.” Touring Car—An open car seating four or more with direct entrance to the tonneau. Coupe—An enclosed automobile seating two or three. Sedan—A closed car seating four or more all in one compartment. Limousine—A closed automobile seating three to five inside, with the driver’s seat outside, covered with a roof. Brougham—A limousine seating three to five with no roof over the driver’s seat. Source: The New York Times, August 20, 1916.  In my first book, The Detroit Electric Scheme, one of the major subplots is the rise and fall of the early electric car. I chose it very deliberately. Not only was I interested in electrics, it was a current hot button story, and to make it even more enticing, most people are unaware that electrics had a history past the 1990’s. I try to tell the truth in my books to the extent I can—I hate reading historicals only to learn that the author has made up what reads like genuine history to fit the story. One of the pleasures I get from writing historicals is solving the puzzle—creating fictional puzzle pieces that fit with the historical ones. Electric cars were popular from before the Twentieth Century until World War I. In fact, in early 1911 there were forty-six different companies building electrics in the United States alone. The most successful of those, Detroit Electric, was the one I chose to write into my story. DE was the most successful of the early electric car manufacturers, reaching number one in sales in the U.S. in 1910 and holding onto that crown while the era of the electrics wound down. I used the founder and company president, William C. Anderson, as the father for my fictional protagonist, Will Anderson. (Mr. Anderson had two daughters. I figured that a man of that time would have liked a son to take over the company business one day, though now that I think of it, I’m certain he would have liked a son other than Will to do that.) I also used a number of the other actual DE employees in minor roles, though I decided to change one name—the man in charge of DE’s battery manufacturing was named Elwood T. Stretch, a name I thought might slow down a reader. I changed it to Elwood Crane, which I thought created a similar mental image. Automotive pioneer Edsel Ford (son of Henry) figured prominently in the book, as did John and Horace Dodge, Charles Kettering, and Henry Leland, who also played important roles. I featured Vito Adamo, Detroit’s first crime boss, who continued on in Motor City Shakedown, book two in the series, which took Will into Detroit’s first mob war. In my opinion, a historical novelist is responsible to history to write the essence of the real historical characters in his books to the best of his ability, to tell the “truth” about who they were, while making up conversations and events. I carefully researched these men so I could feel confident that I could give readers a feel for who they really were. It’s particularly challenging to write historical characters who are well-known and well-documented. An author can’t very well kill off a real person who lived beyond that time, nor, at least in my opinion, should they write those characters doing things they would not have done in real life. I try to blend the person’s actual history with my imagining of what he would have done when thrown into a certain situation in the books. In telling the story of the early electric, I had to write the time period during which the paradigm changed, when the advantage of the electric disappeared. The Detroit Electric Scheme spans from late 1910 to early 1911. As late as January 1911, the electric looked pretty invincible as the automobile for women, city doctors, and urban delivery companies. When Charles Kettering introduced his electric self-starter for gasoline automobiles, that advantage went up in smoke, though it took a couple of years for the shift to be made apparent. Even in a three month time span, I could show how the electric had built into a viable product while also including the event that marked its downfall. I think a historical must be true to history—to the people and events which have been documented. Beyond that, I can do just about anything I like. That’s enough freedom for me. by D.E. Johnson

One of my true pleasures in writing historical novels is finding odd facts to share. My book Detroit Breakdown, sent me down a rabbit hole that I didn’t want to leave. My protagonist was stuck in an insane asylum called Eloise Hospital, which, at the time (1912) was experimenting with radium on tubercular patients. In the early Twentieth Century, scientists discovered that most of the world’s healing hot springs were radioactive. Radon gas (the byproduct of radium deteriorating) was leaching into the water. The springs healed, they were radioactive, ipso facto radiation heals! Soon experiments commenced using radiation to cure health problems. Success was found with both tuberculosis and cancer. Radiation became a sensation on par with electricity in the late Nineteenth Century and the telegraph fifty years earlier. As I researched the radium treatments at Eloise, I started coming across strange curatives that used radium or uranium. The more I looked, the weirder they got. Consider the following: The Revigator (1912 – 1930’s) A uranium-lined water jar that would irradiate water overnight. Their advertising claimed, "The millions of tiny rays that are continuously given off by this ore penetrate the water and form this great HEALTH ELEMENT—RADIO-ACTIVITY. All the next day the family is provided with two gallons of real, healthful radioactive water … nature's way to health." The Revigator Company recommended a daily minimum of six large glasses. It was a smash. They opened branches across the United States and sold tens of thousands of water jars to the public. And not only were Revigators irradiating the water, they also released large amounts of other toxic elements, such was arsenic and lead, into the water. Radithor (1918 – 1932) The most successful of the radioactive curatives with approximately 400,000 bottles sold, Radithor was made of distilled water with a high concentration of two different radium isotopes. Patients were to drink a bottle after a meal. It was advertised to cure stomach cancer and mental illness, as well as restore “vigor and vitality” (a common theme of radium curatives). A playboy/industrialist named Eben Byers was Radithor’s best-known victim. Byers hurt himself falling from a train berth in 1927, and his doctor recommended Radithor to help him heal. (Not coincidentally, doctors received a 17% kickback from Radithor prescriptions—and the stuff wasn’t cheap at $30 a case.) After the first bottle, Byers felt peppier. He figured that if one bottle made him feel better, three would really work. He set out on a three-bottle-a-day regimen of Radithor. When Byers died a painful death from radiation poisoning in 1932, The Wall Street Journal ran this headline over their article: The Radium Water Worked Until His Jaw Came Off Degnen’s Radioactive Eye Applicator (1910’s)—Created by M.L. Degnen, the inventor of the Radio-Active Solar Pad, this product, which looks like a pair of wire-rim glasses with opaque lenses, was available in three strengths, and was advertised to cure headaches and difficulty in focusing, as well as nearsight, farsight, and oldsight. It was recommended that the user close his eyes when using the Applicator. Radione Tablets (1920’s)—“Strength of Iron—Energy of Radium.” Just what they sound like—Radium tablets. For energy! (Nudge, nudge, wink, wink. See Vita Radium suppositories and Radiothor for indications.) Radium Bread (1920’s)—Baked by the Hippman-Blach Company in what is now the Czech Republic, this bread was made with radium-enriched water. Tho-Radia Face Cream (1930’s)—Popular in France, Tho-Radia made a full line of beauty products and perfumes containing both thorium chloride and radium. Is your skin dull, listless? Want a little shine? Try Tho-Radia! The man the company claimed invented the product line, Doctor Alfred Curie, was not a member of the famed Curie family, nor was he even likely a real person. The Scrotal Radioendocrinator (1930’s)—My second favorite product. For a mere $150, you could purchase this gold-plated device, filled with radium, which you would place over your endocrine glands (for men they specified under the scrotum) overnight, for improved endocrine health. The inventor, William Bailey, claimed to have drunk more radioactive water than any living man. He died in 1949 of bladder cancer. And my hands-down favorite … Vita Radium Suppositories (1930s) You don’t need to try too hard to read between the lines of this advertising copy to see that Vita suppositories were allegedly the answer to men’s problems in the bedroom. “Weak Discouraged Men! “Now Bubble Over with Joyous Vitality Through the Use of Glands and Radium ". . . properly functioning glands make themselves known in a quick, brisk step, mental alertness and the ability to live and love in the fullest sense of the word . . . A man must be in a bad way indeed to sit back and be satisfied without the pleasures that are his birthright! . . . Try them and see what good results you get!" (Vita Radium Suppositories are shipped in a plain wrapper for confidentiality.)” These companies had the cure for what ailed you. Unfortunately, no one had a cure for the cure. It’s easy today, a hundred years later, to laugh at the idea of these curatives. But I guarantee you that people in the 1910’s laughed at the ridiculous products that were used a hundred years earlier. What scares me is that a hundred years from now people will be laughing at the harmful products you and I use today. Which ones, do you think? |

AuthorD.E. Johnson: Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed