One of the distinctive (distinktive?) features of Chicago over the last couple of centuries has been the pollution in the Chicago River. The book I'm currently writing (The Resurrectionist's Apprentice) is set in 1874 Chicago. At that time, raw sewage and the offal from the stockyards and slaughterhouses was being dumped directly into the river, which then flowed (most of the time) toward Lake Michigan. By 1869 the river had gotten so disgusting that the city appointed a "Smelling Committee," whose job was to travel up and down the river--in August, the hottest time of year--to report on the water quality. The mayor, sanitary superintendent, the health officer, and others boarded a boat in the main branch of the river, the least offensive area in the city limits, and headed south. Along the way, they encountered a carcass, which some of them thought to be a pig, others a cat, boys who had been swimming whose skin was "tinged by the black water," the noteworthy "Twelfth Street" and "Eighteenth Street" smells, distinctive enough to have their own names, and sights such as "The water came up thick and black. The surface was covered with a filthy froth and bubbles of gas, while a terrible stench rose over the inky water ..." They passed a defunct slaughterhouse with a wretched odor caused by hams decomposing for years in the river, and distilleries that reeked of "two acres of decaying swill." At the end of the trip, the Tribune reporter onboard wrote that "the river is greatly improved since the last inspection." "Bubbly Creek," was a fork of the south branch of the river at the southern boundary of the Union Stockyards. As you might surmise from the name and location, the meatpackers used this body of water as their sewer and dump sight. The decomposition of blood, entrails, and diseased animals caused the creek to bubble night and day. For years, the meatpackers played a game of cat and mouse with the Smelling Committee. When they were forbidden to dump their offal in the river, they began doing so at night, and then only after the posted detectives would leave. Somehow, they always found a way to dump their waste in the river. This made the 1871 attempt to reverse the flow of the river a higher priority of the city's fathers, but the refuse continued to flow through downtown until the successful reversal of the river in 1900, when Chicago began shipping its sewage and slaughterhouse byproducts downriver, and it was no longer their problem.

6 Comments

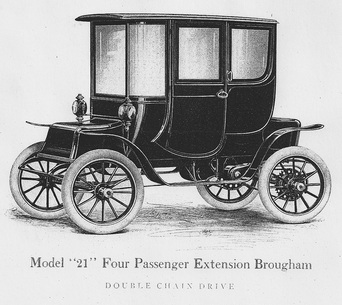

When I began researching early Twentieth Century Detroit for my historical mystery series, I came across all kinds of information about electric cars. I had some vague notion that electrics existed back in the day, but I really had no idea how significant a part they played in automotive history. At the turn of the Twentieth Century, there were almost twice as many electrics on the road as there were gasoline cars, but twenty years later, the quieter, cleaner-running vehicles had all but disappeared. The electric car was a superior design, simpler and more reliable. Yet during an age when gasoline-powered vehicles broke down so often they came from the factory with a repair kit, electrics were wiped out.

That smelled like a conspiracy. After watching Who Killed the Electric Car?, my mind filled with possibilities. As an unpublished author, I needed a conspiracy. At the top of my wish list—a cabal led by Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller conspiring to wipe out electrics. Imagine a conference room at the Standard Oil Company, with Ford and Rockefeller and their henchmen. Rockefeller closes the blinds, strolls to the head of the table, and says, “Gentlemen, we have a problem.” Then, though a series of shady business dealings, they work behind the scenes, manipulating the industry like a pair of puppet masters, probably ordering the murders of a few men along the way, until they squeeze the electric car companies (the good guys) out of business. For the book, I’d need a hero—some dashing electric car whiz kid who’s out to save the world, until he’s crushed by the nefarious forces of evil, led by Big Oil. Can you say “bestseller?” I started digging in with Henry Ford. It wasn’t until late 1908 that he hit on his first successful vehicle—the Model T. Prior to that, he had little to gain with the death of the electric. Okay, so how about later? Turns out Ford wasn’t against his company producing electrics. He and Thomas Edison, who were close friends, discussed the possibility of Ford Motor Company manufacturing electric cars on numerous occasions, but Ford’s engineers were never able to design one they could build cheaply enough for his taste. Further, while Ford had his share of faults (and a few other people’s shares as well), he was a loyal friend. Edison was building batteries for electrics, and it’s hard to imagine Ford cutting him off at the knees like that. I kept digging, but I wasn’t able to come up with any evidence of Ford’s involvement in the conspiracy. So on to Rockefeller and Standard Oil. Talk about a guy with a motive—in the early 1900s he controlled more than 90% of the United States’ oil production and only a little lower percentage of the sales of refined oil products. He had a lot to lose if electrics supplanted gasoline-powered cars. So what did he do? Nothing. Damn it. I could see that number one spot on the New York Times list going up in smoke. Still, I wanted to know. Was it the pope? That would work. How about Teddy Roosevelt? Not quite as sexy, but still good. Andrew Carnegie? J.P. Morgan? Nope. It was me. And you. The consumer killed the early electric. Aided by Charles Kettering. Early electric cars were expensive. The cost of batteries, the technology of which has changed little to this day, was extremely high, putting the price of electrics at a serious premium to gasoline-powered cars. The good news was that automobile owners were rich, because most gasoline cars cost about two year’s wages for the average worker, and most electrics were 50% higher than that. The folks who bought these things were the upper-class, and they could afford any car they wanted. So, if the manufacturers of electrics stuck to the high end, they would have been okay, right? Well, no. There were other problems, such as charging. First of all, you had to be somewhere that had an electric grid, not a given in the early Twentieth Century. Next, you had to leave your car all night to charge it. No quick stop at the gas station and off you go! Range complicated the problem. Most of the early electrics were rated at around fifty miles per charge. That was enough for most uses, but not all, and very few people owned more than one car. By the 1910s, the range of electrics had doubled to 100 miles or more per charge, but still; after 100 miles—if you dared try to take it that far—you were stuck for eight hours or so while your batteries charged. And again, that’s assuming you were somewhere that had electricity. So, electric cars were expensive, took a long time to charge, and had limited range. Sound familiar? But they had one thing going for them—women dug electrics. Why? Because of the reasons you might think: they were quiet and didn’t spew noxious fumes. There was a bigger reason, though. They could be started with the flip of a switch. To start a gasoline-powered car, you had to bend down in front of it, grab hold of the crank, and give it a spin. Talk about unladylike. Woman drivers at this point in history were already progressive, really on the cusp of impropriety. To perform a task such as starting a gas car was unthinkable. The electric car manufacturers focused on their primary demographic—rich women. By doing so, they made electrics de facto women’s cars. It’s not like the men of the early Twentieth Century cornered the market on machismo—men have always wanted to be “manly,” but this was the period in which Teddy Roosevelt’s “Strenuous Life” was the model. Men were men, and by George, they weren’t going to be driving a woman’s automobile. Then, in 1911, Charles Kettering went and designed a self-starter for gasoline cars that allowed drivers to start them by flipping a switch. That was the beginning of the end. Women began choosing their automobiles for reasons other than how they started, and a much wider array of gasoline-powered vehicles offered many tempting choices. By the time World War One wrapped up, electrics were all but gone from the American landscape. Only a few electric car manufacturers survived into the Twenties, and only one that I’ve found (Detroit Electric) made it past the Great Depression, and they scraped along by the skin of their collective teeth until 1939, when they finally gave up. Conspiracy? Unfortunately, no.… Sigh. Bye bye NYT #1. It wasn’t Ford or Rockefeller or Roosevelt or Carnegie or Morgan. Or even Kettering. As the great philosopher Pogo so famously said, “We have met the enemy … and he is us.” Choosing a compelling setting for a historical can be challenging, particularly for a series. An author has to be sure the setting is enough to carry more than a single book. Each new book must illuminate new events, people, or places. (And given that most publishers want a series to remain pretty stationary in terms of locale, that means new places within the overall setting.)

I should note that not all historicals use events the way I do. I suppose it’s the teacher in me that wants to illuminate a bit of history along with an entertaining story, but many historicals are more about the feel of the era, rather than the events. As for me, here’s how it worked: When I started researching The Detroit Electric Scheme, I was pretty sure I wanted to use the early automotive industry as the major backdrop for the book, but as I came across more and more information on the early electric car, I decided to focus the story there. My protagonist became Will Anderson, the son of William C. Anderson, the real president of Detroit Electric, America’s most successful early electric car company. DE made electric cars from 1907 to 1939 and became the number one manufacturer of electrics in 1910. I discovered that the tipping point from success to eventual failure for electrics came in early 1911, so I set the book to end at that point. I also looked for mileposts to use in future books. Fortunately, Detroit has a colorful history that provided me with lots of options. (Back to my point about publishers and locales—I wanted Will to chase the antagonist of the second book to Panama, where the building of the canal would serve as Backdrop II. St. Martin’s Press wanted Will to stay in Detroit, so that book never got written.) Book two, Motor City Shakedown, was originally planned as the third book in the series, and takes Will through the first mob war in Detroit history, a real bloodbath between the Adamo and Gianolla gangs. I kept my eyes and ears open while I was writing those two, looking for a compelling setting within the Detroit of 1912. I kept hearing about this place called Eloise Hospital, which served, among other things, as the Detroit area’s insane asylum for nearly a century and a half. Every other person I talked to around Detroit had some memory of Eloise—usually a relative they had to visit. The memories were uniformly frightening to the individual, with the exception of one man who fondly remembered Sunday picnics on the lawn. (He didn’t have a relative on the inside.) Eloise became the setting for a significant part of Detroit Breakdown, which focuses on mental health treatment a hundred years ago. This was a tipping point from containment to treatment, as psychoanalysis started to come into its own. Eloise Hospital stretched over 900+ acres, with seventy-five buildings and over 10,000 patients and inmates at one time! It was a city unto itself, with farms, bakeries, canneries, sixteen kitchens, a fire department, police department, and a cemetery (which today holds over 7,000 graves, none of which are marked other than with a number, and no index or map has survived). Now I just had to figure out how to get Will inside Eloise. (It wasn’t too challenging, given his lack of stability.) When I finished that book, my options were feeling limited. There was the massive salt mine under the city, which I thought would be interesting, but not enough to carry a book. I could go back to the underworld, but I felt I got enough of that in the second book. Then I realized I had never taken a good look at Detroit politics of the day, and I hit on two major scandals. In the summer of 1912, all but one Detroit aldermen were caught in a bribery sting, elaborately planned and carried out by the detective agency of William Burns, known at the time as “America’s Sherlock Holmes.” At the same time, campaigning was in full swing for the presidential election as well as for a amendment to the Michigan constitution to allow women the vote. (Can you imagine it? Women voting? Many—including many women—couldn’t.) The election was peppered with the kind of voter fraud that can only be found in the Third World these days, and in the end the amendment was defeated. Michigan women had to wait seven more years before they could vote. As I had set up Will’s on-again, off-again girlfriend, Elizabeth Hume, as a suffragist, I was able to fit them into this story as well. So, four books covering the rise and fall of the early electric, Detroit’s first mob war, a huge insane asylum, and political corruption, all taking place between 1910 and 1912. All events and/or places I find compelling. “Now what?” you may ask. The answer—a book set in Chicago. Detroit has been hung with a few nicknames over the years, but it’s probably been a few years since you heard it called the “Paris of the West.” Okay, I know. You’ve never heard it called that. But in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century, before “Motown,” “Motor City,” and more recently, “Murder City,” people called Detroit the “Paris of the West.”

And it was for good reason. It was a beautiful city, full of green space, culture, and stunning architecture. Detroit’s streets were originally laid out by Augustus Woodward in a spoked-wheel design, emulating Washington D.C. The city was filled with parks and wide boulevards. Some of the earliest skyscrapers in the United States were built here around the turn of the century. (At the time, the term “skyscraper” meant a building of ten stories, give or take.) The city had a well-funded and-attended opera, symphony, ballet, and art museum. On top of that, commerce boomed. Detroit became one of the great hubs of manufacturing in the country, leading or being one of the leaders in stoves, cigars, train cars, and a myriad of other items. The city’s location was perfect—ever since the Erie Canal opened in 1825, the Detroit River connected the Great Lakes to New York and the Atlantic. Natural resources were plentiful. Most of Michigan was forest, and its Upper Peninsula was one of the great mining regions of the world. All of this makes for a nice place to live, but it’s a very incomplete picture of Detroit in the early Twentieth Century, which is when my novels are set. Nice places to live are fine and dandy, but not the greatest places to set dark mysteries. Fortunately (for me), the time period and city were layered with much more interesting people and problems. Every city has its “dark underbelly,” and we all expect Detroit’s to be extra dark. You wouldn’t be disappointed. One reason manufacturing was so strong was the Employers Association of Detroit, which acted as a sort of outsourced human resources company for the city’s manufacturers. The EAD specialized in keeping out unions, thereby controlling wages. They planted spies in factories, beat up agitators, and even brought in muscle from organized crime when necessary. Speaking of crime, the newspapers estimated there to be more than 1,000 street gangs in the city in 1910. Sicilian gangs had begun the takeover of the city’s rackets. Illegal importing was a huge moneymaker, because import duties were so high at the time, often doubling the price of an imported item. The Detroit River made a convenient smugglers’ highway, with Canada less than half a mile away from the city. And I can’t write about Detroit crime without including city government. In July 1912, twenty-six of Detroit’s thirty-six aldermen were arrested for bribe-taking, and in true Detroit fashion, by the end of 1914, every one of them had either been acquitted or had the charges dropped. This in spite of the prosecution’s open-and-shut cases against many of them, including audio recordings of the men demanding bribes in one of the earliest uses of wiretapping. Detroit’s people were fascinating. According to the 1910 census, less than 10% of Detroit’s 465,000 residents were even born in the State of Michigan. The rest came over in great waves of emigration, first from Western Europe, primarily Germany and Ireland, and then, in the early Twentieth Century, from Southern and Eastern Europe. The city was a patchwork of ethnic enclaves, like a smaller version of New York City. Most of those people lived in squalor. It was a great time to be alive if you had money, but for the other 99.99%, live was hard—no government social programs like unemployment insurance or welfare, dollar-a-day wages that didn’t feed a family, and crumbling tenements in which to live. The masses from Europe came for the opportunity, and for most the reality didn’t live up to the dream. This mash-up of rich and poor, grand success and sweeping failure, honesty and vice makes for a perfect crucible for stories of people’s experiences, good and bad, with most, like our own personal stories, usually somewhere in between. Writing a historical novel is a balancing act of the modern and the ancient, from current and past ethical boundaries to a balance of two different eras’ literary styles.

On the first topic, I have a friend, Albert A. Bell, who writes ancient Roman mysteries, and his protagonist, Pliny the Younger, is a slave-owner. Part of Albert’s task is to include in Pliny the attitudes the wealthy would have had toward those slaves, while still keeping him a sympathetic character to the reader. It’s a definite balancing act. I don’t know what Pliny really thought about his slaves or how he treated them, but Albert keeps him distanced yet reasonably compassionate and makes it believable. I doubt many Roman slave-owners thought much about their slaves as people, but to the modern mind it’s nearly impossible to feel sympathetic to a character who treats people like cattle (or even in many cases, treats cattle like cattle). Modern readers, for the most part, want a protagonist they can see as a “good guy,” which sometimes blurs the line of historical accuracy. In my books, set in 1910’s Detroit, a person with social status would have been raised with very definite opinions regarding people of color, the poor, and the “insane”—which would have included gay people, who were considered sexual deviants. My protagonist, Will Anderson, was raised in that type of household, and when an openly (or as openly as was possible) gay man tries to befriend him, Will has to rebuff him. Again and again. He accepts the man’s help only when he has exhausted all his alternatives. I felt like I was walking the line there. I wanted to include the historical perspective on homosexuality, but I also wanted this character to be significant in the book. The only way I could do that was to box Will in enough that he had no choice. From there it felt right. On the second topic, writing style has obviously changed a great deal over the years. Even though my books take place only a hundred years ago, if I wrote in the style of the day, most readers would yawn and put down the book halfway through the first chapter. (That’s not strictly true. If I wrote a book in the style of the day, no publisher would touch it, so no one would see it anyway.) Our goal as historical writers needs to be to create the impression of the historical style. Our books are not written in the verbiage, syntax, or particularly the “style” of the time period we write, but are instead our approximation of that language—to create the feeling of authenticity to the reader, while keeping the book moving along. The most common method employed is to use loftier language for the well-to-do. With most historicals set in the U.S., I tend to read with an English accent. And there is a definite reality to that. Depending on time and place, it wasn’t unusual to hear and educated American speaking much more like a Brit. However, poor people did not speak that way—in America or anywhere else. They used terrible grammar and had horrible vocabularies, and many of them swore like stevedores. (How’s that for a historical word?) I personally get suspicious when I’m reading a book in which the peasants speak like nobility. Okay, there probably was one—somewhere—but the other millions of poor folks didn’t even know anyone who talked like that. They didn’t go to school. They didn’t read. Heck, they didn’t bathe. When survival is the rule of the day, language tends to be left behind. I imagine this is a somewhat contentious issue, so what do you think? Should historical writers strive for absolute historical accuracy, or should they write in a way that readers will find more accessible? You’ve seen which side I come down on. How about you? By definition, historical fiction is a lie.

It’s made up. Not true. Otherwise it would be history. Writers deal with that fact in a variety of ways. Some will simply pick a historical backdrop and write a completely fictional story set in their approximation of that time and place. Others will look for real events and people, and fit their fictional characters within the real story of those events and people, and still others will write their imagining of how a real story with real people took place, staying true to the historical record as best they can. And the last category—one I personally find perplexing—is to take real historical characters and make them the protagonist in stories in which they do things they never did or even would have done in their real lives. Most historical readers have a passion for real history, so there don’t seem to be many books published these days in the first style. Traditionally, a historical romance (Has the name changed yet to “historical erotica?” Lord, I hope not.) would most often be written as a completely fictional tale set in a historical environment. A time and place is chosen for the story, and away we go with the dashing prince and the lowly servant girl. Most historicals fall into the second category—real events takes place, and some of the characters are real historical characters, but the protagonist and other key characters are fictional. This is what I do. I find interesting history (the rise and fall of the electric car in the early Twentieth Century, the first mob war in Detroit history, the largest insane asylum in the U.S. and mental health treatment a hundred years ago, and the battle for women’s suffrage) and create a story that will fit within that backdrop. My books are mysteries, so of course there are bodies, and those stories are - usually - fictional. However, it’s important to me to be as accurate as I can in describing the people, places, and events that were really there. I like to learn as I am entertained, so when I read about an ancient (or not so ancient) time and place, I enjoy the little history lesson included (as, I suspect, do you, the reader of this post). The third style—fictionalizing real events and characters only as much as the historical record doesn’t detail—is a tricky one to pull off. Some writers do this incredibly well. They tell a real story but include unknown dialogue and some unknown actions—but only those that have a significant impact on the true story. It’s a “just the facts, ma’am” approach, so obviously they need a great story to start out with. These books are almost always “one-offs,” as it would be very difficult to write an interesting series that sticks to the truth. The story of the Battle of Gettysburg or Machine Gun Kelly will be fascinating, but what do you write when the battle is done or the criminal is killed? (And this is not to say that I don’t love this style. Some of my favorite historicals are real stories that have been “novelized.”) With an apology to those of you who write or enjoy the last style—taking a real person and having them do things the real person would not have done—I simply don’t get it. And many of these are or have been popular books: Edgar Allan Poe, Jane Austen, Ernest Hemingway, Humphrey Bogart, even Groucho Marx and Elvis Presley—solving crimes? Say what? Throw in some zombies and we’ve really got a party going. Okay, maybe I’m overstating it. If the book is camp (as I imagine the Marx and Presley books to be), then I understand the entertainment value. If the story gives readers another book written in the style of a favorite author, then I guess I understand that too. I suppose I’m hung up on the other possibility—that the story better illuminates the character. Why not write about something they really did? If it’s not interesting enough, then why not find another character? What’s your favorite style, and why?  I’ve chosen a place and time period that is recent and populous enough to have a strong historical record, which makes my research easier than it might otherwise be. Detroit in the 1910’s had three very popular newspapers, and the archives still exist for all three, with each on microfilm. In addition, I’ve written a lot about the early electric car industry, and, as you might expect, there are some great sources for automotive history in the Detroit area, my favorite being the Benson Ford Research Center at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. My first novel, The Detroit Electric Scheme, was set against the backdrop of the rise and fall of the early electric car industry. I chose Detroit Electric to be my “sample” company. The real Detroit Electric was the most successful electric car manufacturer in United States history and made cars from 1907 to 1939. (Unfortunately, their greatest successes all came prior to World War I.) The Benson Ford has a wealth of information on Detroit Electric, helped by the fact that Henry Ford bought three of them, two for his wife Clara and the other for his son Edsel. (Edsel quickly grew out of the DE. It simply wasn’t fast enough for him.) I was able to get copies of detailed sales brochures, owner’s and operating manuals, pictures, and correspondence, including original letters from Thomas Edison to William C. Anderson, the owner of Detroit Electric. That was pretty exciting for a history nerd like me. I also have to mention the National Automotive History Collection at the Detroit Public Library. This is another great source of information, though they are not as well-funded as the Benson Ford, and it takes a little more work to get the information you need. So, automotive history is easy. Still, there are challenges. My second book, Motor City Shakedown, is set during Detroit’s first mob war in 1912 and 1913. I decided to write this book for two reasons—I, like most people, am interested in organized crime history, and I could find almost no mention of this war in history books, which really surprised me. New York and Chicago mafia history is well-documented, but little is known about the gangsters who ruled Detroit prior to Prohibition. In this case it was two Sicilian gangs—the Adamos and the Gianollas—who were battling for control of the Detroit rackets. Vito Adamo had taken over leadership of a very loosely-organized group of gangs in Detroit’s Little Italy and downriver areas, and Tony Gianolla and his brothers wanted what Vito had. By the time the issue was settled, dozens of men had been shotgunned in the streets of Detroit, all in about a nine-block area. Fortunately for me, the newspapers were filled with stories of this war every day for months. Detroiters followed the sensational news with rapture—this kind of thing didn’t happen in the “Paris of the West.” The war was finally settled in November 1913, when two of the brothers were murdered. (I’ll leave out which brothers, as it is in the climax of Motor City Shakedown. You can easily Google it if you’re curious.) Newspapers have many other benefits as well. Weather can be helpful. For the closing night in The Detroit Electric Scheme, it had really been so foggy you could barely see your hand in front of your face. Nice detail for a book. Advertisements are excellent for seeing what was popular and the kind of prices the products commanded. And, of course, news and editorial gives great insight as to what people were thinking about, an absolute necessity in getting into their heads well enough to presume I can write from the perspective of one of theirs. I can’t leave out the internet (though sometimes I’d like to). This needs to be approached with caution, because there is a lot of crap out there, but a wealth of information has been made available online. My third book, Detroit Breakdown, is set largely in Eloise Hospital, the Detroit-area insane asylum. A Google e-book entitled History of Eloise was originally published in 1913 (my book is set in 1912) and shows a (very one-sided) history of the institution and, best of all, contained detailed descriptions of the buildings and the classifications of the residents. (For an institution that at one time had seventy-five buildings on over 900 acres, serving 10,000 patients at a time, it would have been challenging to construct something approaching the 1912 reality without that book.) Of course, printed books are often a good source of information about places and time periods as well. Of particular interest to me are books about the social and cultural issues and norms of the time period. The greatest challenge in writing a historical novel is being able to put oneself in the head of a person inhabiting that time and place. While understanding the “who’s,” “what’s,” and “where’s” is critical in creating a credible historical novel, nothing is more important than understanding the “why’s.”  I’ve thought a lot about the purpose of historical fiction and what it provides readers. I’ve always enjoyed being entertained while also learning about something new, which I had thought was enough. But recently, while listening to a podcast on history while I was driving, I kept tuning out and had to force myself back to what the person was saying, because I was interested in knowing what happened. Finally I made it through, and I thought about it. The story was interesting enough that it ought to have kept me going, so I wrote off my disinterest as having other things on my mind. Then I realized I had no context for the story. I didn’t understand why the people did what they did, and the podcast was simply a recitation of facts, much like our children have to listen to in their history and social studies classes. The teacher drones on about Henry Ford or America’s Progressive Era, and the students are expected to memorize the facts and regurgitate them on a test. Why would they care about these long-ago people? Of course the answer that probably came to your mind is that those who forget history are doomed to repeat it, but that isn’t likely in the top 1,000,000 concerns for the average high school student these days. But what if they knew that Henry Ford mercilessly drove his only son to his death, that he was a rabid believer in the dominion of Jewish bankers over the world, that his famous “Four-Dollar Day” was an effort to decrease employee turnover that stood at 300% a year? Or that the Progressive Era was caused by the revulsion felt by the rich and rising middle class that immigrant children were starving on the streets of the United States by the thousands, that millions were forced to beg and steal to live through another day, and the government was doing nothing for them? That’s what we do—provide that context. Facts are cold and uninteresting to most—this war started here and ended there, this man ruled from this time to that time, etc. (And often facts aren’t facts. They were written by the side that won. But that’s another story.) If I can immerse a reader into an immigrant’s life in 1910 Detroit as well as into the lives of the era’s wealthy, I have provided context to the social struggles that ensued. History so often provides the what, where, and when, but it usually leaves out the why, which is all-important. Why did millions of Germans stand by and allow Hitler his atrocities? Were they bad people? No. There were complex social and historical factors at play, as well as masterful manipulation of the press. What they knew, what they believed to be true, was different than what history remembers. Until history teachers are allowed to teach the humanness of history and not rote memorizations of fact, we have to provide the “why’s.” That feels like a pretty useful way to spend a life.  I could cite a great number of historicals here, because there truly are so many that are outstanding, but I’ll choose only two: Ironweed by William Kennedy, and The Road to Wellville by T.C. Boyle. You might find it interesting that neither of them are crime novels, given that that's what I write, but these are a couple of damn good books. Ironweed, which won a Pulitzer Prize in fiction, completes Kennedy’s “Albany Cycle,” a marvelous three-book series set in and around Albany, New York. The cycle starts with Legs, the story of 1920’s and ’30’s gangster Jack “Legs” Diamond, as told by attorney Marcus Gorman. The second, Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game, takes the titular character, a small-time and tarnished gambler during the Great Depression, through a harrowing kidnapping story. The cycle finishes only a few weeks after the end of book two, with Ironweed, the story of Billy Phelan’s father, Francis, who returns to Albany with Helen, his companion and fellow hobo. In his youth, Francis was a baseball player with major league potential and ambitions until he lost a finger in a fight. He fled Albany after dropping his thirteen-day-old son, Gerald, killing him. Decades later he returns to Albany to face the ghosts of his past, both literally and figuratively. Here’s how the book starts: “Riding up the winding road of Saint Agnes Cemetery in the back of the rattling old truck, Francis Phelan became aware that the dead, even more than the living, settled down in neighborhoods. The truck was suddenly surrounded by fields of monuments and cenotaphs of kindred design and striking size, all guarding the privileged dead. But the truck moved on and the limits of mere privilege became visible, for here now came the acres of truly prestigious death; illustrious men and women, captains of life without their diamonds, furs, carriages, and limousines, but buried in pomp and glory, vaulted in great tombs built like heavenly safe deposit boxes, or parts of the Acropolis. And ah yes, here too, inevitably, came the flowing masses, row upon row of them under simple headstones and simpler crosses. Here was the neighborhood of the Phelans.” Ironweed is a story of guilt and redemption, or such redemption as one can find in this life. It is at once violent and tender, hateful and loving. In my opinion, this is a masterpiece of American literature. My favorite book of all time. The Road to Wellville is a very different book. I hadn’t read any of Boyle’s previous novels when I came across it lying on a new fiction table at a local bookstore. The cover looked interesting, and the cover flap info showed it was set in Battle Creek, Michigan, which is only about 30 miles from where I live. I read a few random pages and decided I immediately needed to devour it. The Road to Wellville is one of those rare books that create grief about halfway through—a book so good and so much fun to read that I start to feel sad that I am going to finish it and will no longer be able to look forward to reading it every day. I come across those only every few years, and they all get reread. Boyle brilliantly skewers the health industry of the early Twentieth Century with the story of Will Lightbody, who is dragged to the Battle Creek “San” (sanitarium) by his grieving wife, who had recently miscarried their child. John Harvey Kellogg, the founder and head doctor of the San, leads the patients with his brand of healthfulness, much of which is on the mark, with a few notable exceptions like radium treatment. Kellogg was a real man and was very influential at the time. He created the breakfast cereal industry and could certainly be described as a force of nature, which Boyle brings to the fore in this book. Here’s how it starts: “Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, inventor of the corn flake and peanut butter, not to mention caramel-cereal coffee, Bromose, Nuttolene and some seventy-five other gastrically correct foods, paused to level his gaze on the heavyset woman in the front row. He was having difficulty believing what he'd just heard. As was the audience, judging from the gasp that arose after she'd raised her hand, stood shakily and demanded to know what was so sinful about a good porterhouse steak--it had done for the pioneers, hadn't it? And for her father and his father before him? “The Doctor pushed reflectively at the crisp white frames of his spectacles. To all outward appearances he was a paradigm of concentration, a scientist formulating his response, but in fact he was desperately trying to summon her name--who was she, now? He knew her, didn't he? That nose, those eyes . . . he knew them all, knew them by name, a matter of pride . . . and then, in a snap, it came to him: Tindermarsh. Mrs. Violet. Complaint, obesity. Underlying cause, autointoxication. Tindermarsh. Of course. He couldn't help feeling a little self-congratulatory flush of pride--nearly a thousand patients and he could call up any one of them as plainly as if he had their charts spread out before him . . . . But enough of that—the audience was stirring, a monolithic force, one great naked psyche awaiting the hand to clothe it. Dr. Kellogg cleared his throat.” You want to know what he says, don’t you? Get the book!  by D.E. Johnson Detroit has been overshadowed by New York and Chicago when it comes to organized crime, but it has plenty of history of its own. One of the reasons I chose the time period I did for my series (1910 – 1913) was that it coincided with the city’s first mob war. Vito Adamo was a Sicilian immigrant who came to America around 1900. He was a grocer in a little town called Ford City, which is now a part of Wyandotte, in the general area described by most Detroiters as “downriver.” He was, of course, more than a grocer, but I mention it because he had some competition across the street—the Gianolla brothers, who opened a grocery a few years after he did. Vito and his brother, Salvatore, had systematically gained control over the Sicilian and Italian crime of the time, both in Ford City, which had a large Italian population, and in Detroit’s Little Italy. That crime included the Black Hand (the protection racket), illegal immigration (Canada is right across the river from the city), importation of duty-free goods (the U.S. was very protectionist at the time, and duties could as much as double the sale prices of foreign goods), and, of course, the “numbers,” or Italian lottery. It was beer sales, however, that started things with the Gianollas. The Adamos had a stranglehold on beer sales in the area they controlled, which was virtually all the territory available to a Sicilian gang at the time. Tony Gianolla saw opportunity and went to the Adamo’s customers with a significant cut in beer prices. When faced with the lost business, Vito Adamo decided to match the prices and throw in ice, a necessity at the time. The Gianollas took umbrage at this and beat up a few delivery drivers. This led to retaliation by the Adamos and, finally, to a shotgun war on the streets of Detroit. Prior to this, the Adamos were unknown to the Detroit police, and the Gianollas had only recently become suspects in the gruesome murder of a former associate. The Ford City police had raided the Gianolla’s store and confiscated about $2,000 in illegal olive oil. ($2,000 was about a year-and-a-half’s wages for a laborer in 1913—a lot of money.) Tony Gianolla suspected a man named Sam Buendo of ratting them out to the police. Buendo’s mutilated and burned body was found shortly thereafter in a nearby field. As the war between the gangs ramped up, the police were still unclear as to the identity of the factions. The close-range shotgun executions, which was really what these murders amounted to, occurred throughout 1913, and were plastered across the front page of the Detroit newspapers for the better part of a year. Both sides lost soldiers until November, when members of the Gianolla gang caught Vito and Salvatore Adamo unawares and gunned them down. The remaining members of the Adamo gang scattered to the wind, and the Gianollas became the bosses—until they were brutally murdered six years later by an associate named John Vitale, who was next in line to run things. An interesting side note is that after Vito Adamo was killed, the police searched his home and found a notebook with pages full of Italian writing and drawings of murder scenes, such as stilettos plunging into men’s backs. The newspapers reported that this might be the break the police had been looking for—a detailed description of the events of the war as well as the players involved. When they had it translated, they found that Vito Adamo was an aspiring author. The notebook was his attempt at a dime novel and was the story of a poor Sicilian boy who resorted to murder only as revenge when persecuted beyond all reason. Perhaps Vito Adamo felt that he was that boy. History remembers him differently. |

AuthorD.E. Johnson: Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed