I’ve chosen a place and time period that is recent and populous enough to have a strong historical record, which makes my research easier than it might otherwise be. Detroit in the 1910’s had three very popular newspapers, and the archives still exist for all three, with each on microfilm. In addition, I’ve written a lot about the early electric car industry, and, as you might expect, there are some great sources for automotive history in the Detroit area, my favorite being the Benson Ford Research Center at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. My first novel, The Detroit Electric Scheme, was set against the backdrop of the rise and fall of the early electric car industry. I chose Detroit Electric to be my “sample” company. The real Detroit Electric was the most successful electric car manufacturer in United States history and made cars from 1907 to 1939. (Unfortunately, their greatest successes all came prior to World War I.) The Benson Ford has a wealth of information on Detroit Electric, helped by the fact that Henry Ford bought three of them, two for his wife Clara and the other for his son Edsel. (Edsel quickly grew out of the DE. It simply wasn’t fast enough for him.) I was able to get copies of detailed sales brochures, owner’s and operating manuals, pictures, and correspondence, including original letters from Thomas Edison to William C. Anderson, the owner of Detroit Electric. That was pretty exciting for a history nerd like me. I also have to mention the National Automotive History Collection at the Detroit Public Library. This is another great source of information, though they are not as well-funded as the Benson Ford, and it takes a little more work to get the information you need. So, automotive history is easy. Still, there are challenges. My second book, Motor City Shakedown, is set during Detroit’s first mob war in 1912 and 1913. I decided to write this book for two reasons—I, like most people, am interested in organized crime history, and I could find almost no mention of this war in history books, which really surprised me. New York and Chicago mafia history is well-documented, but little is known about the gangsters who ruled Detroit prior to Prohibition. In this case it was two Sicilian gangs—the Adamos and the Gianollas—who were battling for control of the Detroit rackets. Vito Adamo had taken over leadership of a very loosely-organized group of gangs in Detroit’s Little Italy and downriver areas, and Tony Gianolla and his brothers wanted what Vito had. By the time the issue was settled, dozens of men had been shotgunned in the streets of Detroit, all in about a nine-block area. Fortunately for me, the newspapers were filled with stories of this war every day for months. Detroiters followed the sensational news with rapture—this kind of thing didn’t happen in the “Paris of the West.” The war was finally settled in November 1913, when two of the brothers were murdered. (I’ll leave out which brothers, as it is in the climax of Motor City Shakedown. You can easily Google it if you’re curious.) Newspapers have many other benefits as well. Weather can be helpful. For the closing night in The Detroit Electric Scheme, it had really been so foggy you could barely see your hand in front of your face. Nice detail for a book. Advertisements are excellent for seeing what was popular and the kind of prices the products commanded. And, of course, news and editorial gives great insight as to what people were thinking about, an absolute necessity in getting into their heads well enough to presume I can write from the perspective of one of theirs. I can’t leave out the internet (though sometimes I’d like to). This needs to be approached with caution, because there is a lot of crap out there, but a wealth of information has been made available online. My third book, Detroit Breakdown, is set largely in Eloise Hospital, the Detroit-area insane asylum. A Google e-book entitled History of Eloise was originally published in 1913 (my book is set in 1912) and shows a (very one-sided) history of the institution and, best of all, contained detailed descriptions of the buildings and the classifications of the residents. (For an institution that at one time had seventy-five buildings on over 900 acres, serving 10,000 patients at a time, it would have been challenging to construct something approaching the 1912 reality without that book.) Of course, printed books are often a good source of information about places and time periods as well. Of particular interest to me are books about the social and cultural issues and norms of the time period. The greatest challenge in writing a historical novel is being able to put oneself in the head of a person inhabiting that time and place. While understanding the “who’s,” “what’s,” and “where’s” is critical in creating a credible historical novel, nothing is more important than understanding the “why’s.”

0 Comments

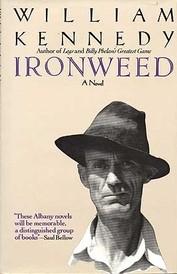

I’ve thought a lot about the purpose of historical fiction and what it provides readers. I’ve always enjoyed being entertained while also learning about something new, which I had thought was enough. But recently, while listening to a podcast on history while I was driving, I kept tuning out and had to force myself back to what the person was saying, because I was interested in knowing what happened. Finally I made it through, and I thought about it. The story was interesting enough that it ought to have kept me going, so I wrote off my disinterest as having other things on my mind. Then I realized I had no context for the story. I didn’t understand why the people did what they did, and the podcast was simply a recitation of facts, much like our children have to listen to in their history and social studies classes. The teacher drones on about Henry Ford or America’s Progressive Era, and the students are expected to memorize the facts and regurgitate them on a test. Why would they care about these long-ago people? Of course the answer that probably came to your mind is that those who forget history are doomed to repeat it, but that isn’t likely in the top 1,000,000 concerns for the average high school student these days. But what if they knew that Henry Ford mercilessly drove his only son to his death, that he was a rabid believer in the dominion of Jewish bankers over the world, that his famous “Four-Dollar Day” was an effort to decrease employee turnover that stood at 300% a year? Or that the Progressive Era was caused by the revulsion felt by the rich and rising middle class that immigrant children were starving on the streets of the United States by the thousands, that millions were forced to beg and steal to live through another day, and the government was doing nothing for them? That’s what we do—provide that context. Facts are cold and uninteresting to most—this war started here and ended there, this man ruled from this time to that time, etc. (And often facts aren’t facts. They were written by the side that won. But that’s another story.) If I can immerse a reader into an immigrant’s life in 1910 Detroit as well as into the lives of the era’s wealthy, I have provided context to the social struggles that ensued. History so often provides the what, where, and when, but it usually leaves out the why, which is all-important. Why did millions of Germans stand by and allow Hitler his atrocities? Were they bad people? No. There were complex social and historical factors at play, as well as masterful manipulation of the press. What they knew, what they believed to be true, was different than what history remembers. Until history teachers are allowed to teach the humanness of history and not rote memorizations of fact, we have to provide the “why’s.” That feels like a pretty useful way to spend a life.  I could cite a great number of historicals here, because there truly are so many that are outstanding, but I’ll choose only two: Ironweed by William Kennedy, and The Road to Wellville by T.C. Boyle. You might find it interesting that neither of them are crime novels, given that that's what I write, but these are a couple of damn good books. Ironweed, which won a Pulitzer Prize in fiction, completes Kennedy’s “Albany Cycle,” a marvelous three-book series set in and around Albany, New York. The cycle starts with Legs, the story of 1920’s and ’30’s gangster Jack “Legs” Diamond, as told by attorney Marcus Gorman. The second, Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game, takes the titular character, a small-time and tarnished gambler during the Great Depression, through a harrowing kidnapping story. The cycle finishes only a few weeks after the end of book two, with Ironweed, the story of Billy Phelan’s father, Francis, who returns to Albany with Helen, his companion and fellow hobo. In his youth, Francis was a baseball player with major league potential and ambitions until he lost a finger in a fight. He fled Albany after dropping his thirteen-day-old son, Gerald, killing him. Decades later he returns to Albany to face the ghosts of his past, both literally and figuratively. Here’s how the book starts: “Riding up the winding road of Saint Agnes Cemetery in the back of the rattling old truck, Francis Phelan became aware that the dead, even more than the living, settled down in neighborhoods. The truck was suddenly surrounded by fields of monuments and cenotaphs of kindred design and striking size, all guarding the privileged dead. But the truck moved on and the limits of mere privilege became visible, for here now came the acres of truly prestigious death; illustrious men and women, captains of life without their diamonds, furs, carriages, and limousines, but buried in pomp and glory, vaulted in great tombs built like heavenly safe deposit boxes, or parts of the Acropolis. And ah yes, here too, inevitably, came the flowing masses, row upon row of them under simple headstones and simpler crosses. Here was the neighborhood of the Phelans.” Ironweed is a story of guilt and redemption, or such redemption as one can find in this life. It is at once violent and tender, hateful and loving. In my opinion, this is a masterpiece of American literature. My favorite book of all time. The Road to Wellville is a very different book. I hadn’t read any of Boyle’s previous novels when I came across it lying on a new fiction table at a local bookstore. The cover looked interesting, and the cover flap info showed it was set in Battle Creek, Michigan, which is only about 30 miles from where I live. I read a few random pages and decided I immediately needed to devour it. The Road to Wellville is one of those rare books that create grief about halfway through—a book so good and so much fun to read that I start to feel sad that I am going to finish it and will no longer be able to look forward to reading it every day. I come across those only every few years, and they all get reread. Boyle brilliantly skewers the health industry of the early Twentieth Century with the story of Will Lightbody, who is dragged to the Battle Creek “San” (sanitarium) by his grieving wife, who had recently miscarried their child. John Harvey Kellogg, the founder and head doctor of the San, leads the patients with his brand of healthfulness, much of which is on the mark, with a few notable exceptions like radium treatment. Kellogg was a real man and was very influential at the time. He created the breakfast cereal industry and could certainly be described as a force of nature, which Boyle brings to the fore in this book. Here’s how it starts: “Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, inventor of the corn flake and peanut butter, not to mention caramel-cereal coffee, Bromose, Nuttolene and some seventy-five other gastrically correct foods, paused to level his gaze on the heavyset woman in the front row. He was having difficulty believing what he'd just heard. As was the audience, judging from the gasp that arose after she'd raised her hand, stood shakily and demanded to know what was so sinful about a good porterhouse steak--it had done for the pioneers, hadn't it? And for her father and his father before him? “The Doctor pushed reflectively at the crisp white frames of his spectacles. To all outward appearances he was a paradigm of concentration, a scientist formulating his response, but in fact he was desperately trying to summon her name--who was she, now? He knew her, didn't he? That nose, those eyes . . . he knew them all, knew them by name, a matter of pride . . . and then, in a snap, it came to him: Tindermarsh. Mrs. Violet. Complaint, obesity. Underlying cause, autointoxication. Tindermarsh. Of course. He couldn't help feeling a little self-congratulatory flush of pride--nearly a thousand patients and he could call up any one of them as plainly as if he had their charts spread out before him . . . . But enough of that—the audience was stirring, a monolithic force, one great naked psyche awaiting the hand to clothe it. Dr. Kellogg cleared his throat.” You want to know what he says, don’t you? Get the book! |

AuthorD.E. Johnson: Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed