I’ve chosen a place and time period that is recent and populous enough to have a strong historical record, which makes my research easier than it might otherwise be. Detroit in the 1910’s had three very popular newspapers, and the archives still exist for all three, with each on microfilm. In addition, I’ve written a lot about the early electric car industry, and, as you might expect, there are some great sources for automotive history in the Detroit area, my favorite being the Benson Ford Research Center at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. My first novel, The Detroit Electric Scheme, was set against the backdrop of the rise and fall of the early electric car industry. I chose Detroit Electric to be my “sample” company. The real Detroit Electric was the most successful electric car manufacturer in United States history and made cars from 1907 to 1939. (Unfortunately, their greatest successes all came prior to World War I.) The Benson Ford has a wealth of information on Detroit Electric, helped by the fact that Henry Ford bought three of them, two for his wife Clara and the other for his son Edsel. (Edsel quickly grew out of the DE. It simply wasn’t fast enough for him.) I was able to get copies of detailed sales brochures, owner’s and operating manuals, pictures, and correspondence, including original letters from Thomas Edison to William C. Anderson, the owner of Detroit Electric. That was pretty exciting for a history nerd like me. I also have to mention the National Automotive History Collection at the Detroit Public Library. This is another great source of information, though they are not as well-funded as the Benson Ford, and it takes a little more work to get the information you need. So, automotive history is easy. Still, there are challenges. My second book, Motor City Shakedown, is set during Detroit’s first mob war in 1912 and 1913. I decided to write this book for two reasons—I, like most people, am interested in organized crime history, and I could find almost no mention of this war in history books, which really surprised me. New York and Chicago mafia history is well-documented, but little is known about the gangsters who ruled Detroit prior to Prohibition. In this case it was two Sicilian gangs—the Adamos and the Gianollas—who were battling for control of the Detroit rackets. Vito Adamo had taken over leadership of a very loosely-organized group of gangs in Detroit’s Little Italy and downriver areas, and Tony Gianolla and his brothers wanted what Vito had. By the time the issue was settled, dozens of men had been shotgunned in the streets of Detroit, all in about a nine-block area. Fortunately for me, the newspapers were filled with stories of this war every day for months. Detroiters followed the sensational news with rapture—this kind of thing didn’t happen in the “Paris of the West.” The war was finally settled in November 1913, when two of the brothers were murdered. (I’ll leave out which brothers, as it is in the climax of Motor City Shakedown. You can easily Google it if you’re curious.) Newspapers have many other benefits as well. Weather can be helpful. For the closing night in The Detroit Electric Scheme, it had really been so foggy you could barely see your hand in front of your face. Nice detail for a book. Advertisements are excellent for seeing what was popular and the kind of prices the products commanded. And, of course, news and editorial gives great insight as to what people were thinking about, an absolute necessity in getting into their heads well enough to presume I can write from the perspective of one of theirs. I can’t leave out the internet (though sometimes I’d like to). This needs to be approached with caution, because there is a lot of crap out there, but a wealth of information has been made available online. My third book, Detroit Breakdown, is set largely in Eloise Hospital, the Detroit-area insane asylum. A Google e-book entitled History of Eloise was originally published in 1913 (my book is set in 1912) and shows a (very one-sided) history of the institution and, best of all, contained detailed descriptions of the buildings and the classifications of the residents. (For an institution that at one time had seventy-five buildings on over 900 acres, serving 10,000 patients at a time, it would have been challenging to construct something approaching the 1912 reality without that book.) Of course, printed books are often a good source of information about places and time periods as well. Of particular interest to me are books about the social and cultural issues and norms of the time period. The greatest challenge in writing a historical novel is being able to put oneself in the head of a person inhabiting that time and place. While understanding the “who’s,” “what’s,” and “where’s” is critical in creating a credible historical novel, nothing is more important than understanding the “why’s.”

0 Comments

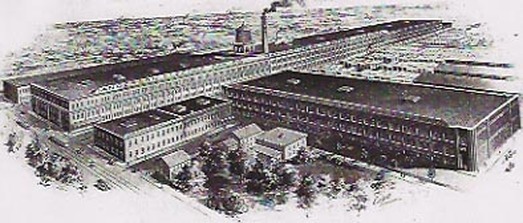

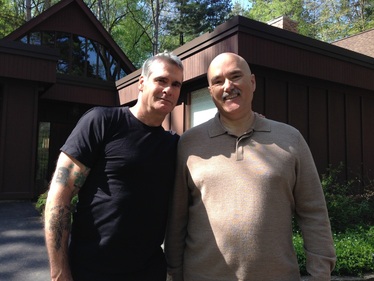

Detroit Electric Factory, Clay Avenue, Detroit, 1911 Detroit Electric Factory, Clay Avenue, Detroit, 1911 (Reprinted from Michigan History Magazine) Are electric cars in Detroit a new concept? Not hardly. The first such vehicles debuted on the streets of the Motor City more than 100 years ago. With names like Century, Detroit Electric, Flanders, Grinnell, and Hupp-Yeats, these no-crank automobiles (and some trucks) appealed to doctors and delivery men because of their quick and easy startups. Women were another strong customer category; the absence of the crank as well as a lack of noise and noxious fumes were viewed as very appealing features to the distaff side. Detroit dominated the gasoline-powered automobile business in the early 1900s, but many people don’t know about the city’s simultaneous foray into electrics, which included the most successful electric car company in U.S. history. The manufacturers of electrics had a heady 20 years or so during which their possibilities looked endless. But a number of factors combined to seal their fate, and they had all but disappeared from the Michigan landscape by the end of World War I. The first electric car was built in Scotland in 1837, although it wasn’t until 1896 that the first American-made production electrics were offered by the Pope Manufacturing Company of Boston, Massachusetts and the American Electric Vehicle Company (later Waverly Electric) of Chicago, Illinois. By the turn of the century, 38 percent of all the automobiles on American roads were electrics. (Forty percent were steam-powered and the remaining 22 percent used gasoline.) The first car to go more than a mile a minute was an electric, as were the winners of the first track race and the first hill-climbing contest. In 1900, there were 75 electric car companies in the U.S. (although many folded before producing anything more than a prototype). By the end of the decade, that number had been whittled down to 46, almost all of them different from the ones that existed 10 years earlier. Every month, more came in and just as quickly went out. Targeted Marketing By 1910, electric cars were marketed toward three distinct customers: rich women, city doctors, and urban delivery companies. For doctors and delivery companies, the benefit was obvious. They made frequent stops throughout their day, and using the manual “crank” starter on a gasoline-powered vehicle was inconvenient and sometimes dangerous. (Some people were even killed when the engine kicked back and the crank spun unexpectedly.) Further, electrics had plenty of range—50 to 100 miles per charge, depending on the model—to cover the necessary distances without worry. Women were also concerned about the starter. The process of bending down, grabbing hold of the crank, and giving it a spin was considered unladylike. Women who drove were already at the edge of what might be considered socially acceptable, and that additional bit of manual labor was too much for many modern women to stomach. The price of batteries (of the lead-acid variety, as you would find today) drove the cost of electric cars to exceed the price of comparable gas automobiles by at least 50 percent. But the ease of starting, combined with the lack of noise and noxious fumes, earned a place for the electric in American society. Detroit’s Contributions At least half a dozen electric car companies were formed in Detroit in the early 20th century: Century, Columbian, Detroit Electric, Flanders, Grinnell, and Hupp-Yeats. Columbian was short-lived and produced only a handful of automobiles, but the other manufacturers each had some measure of success. All of these companies advertised a range of up to 100 miles on a charge—more than enough distance in an era of 10-mile-per-hour speed limits and barely passable rural roads. The primary market for electric cars after 1910 was at the high end, with models priced at $2,500 and up. Given this, some companies thought they saw an opportunity for a less expensive automobile to succeed. One such company was Century Electric, which operated from 1912 to 1915. Century made lighter-weight cars with a long, underslung chassis that was hung below the axles rather than set atop them. This last feature lowered the vehicle’s center of gravity, making it safer to round tight corners at high speeds. Century manufactured open-body roadsters (available at only $1,250 in 1912) as well as enclosed broughams, which looked similar to opera coaches. These days, Century is little more than an asterisk in the history of the electric car. Flanders Electric debuted in 1912 and was the brainchild of Walter Flanders, Henry Ford’s former production manager and the “F” in the E-M-F automobile company. The Pontiac auto maker was successful in the gasoline-car market with its “Flanders 6,” but saw an opportunity to build electrics as well. It made plans to take over the market, pricing its electrics from $1,775 to $2,500. The Flanders’ look was notable for the absence of a hood; the company’s brochures even ridiculed electric car companies that chose to add that needless feature. Electric-car motors were placed under the automobile—or, in the case of Flanders’ cars, in the back because they were built low to the ground—so there was no need for a traditional hood, other than for aesthetic reasons. It’s said that Flanders spent the better part of a million dollars promoting its product line. After producing fewer than 100 electric cars and finding itself in receivership, Flanders entered the history books in 1914. The Grinnell Electric Car Company was owned by the same family as the Grinnell Brothers Piano Company. Grinnell’s automobiles, manufactured from 1913 to 1914, were reminiscent of the products of industry leaders such as Baker—a prominent Ohio brand—both in design and in customer focus. The company aimed at the high-end market, and primarily built enclosed-body coupes and broughams that ranged from $2,800 to $3,400. Grinnell did little to differentiate itself from its competitors, though, and soon found its cars on the scrap heap. Hupp-Yeats Electric was one of the more successful electric car companies of the era. The company was founded by Robert Hupp of Hupmobile fame and was in business from 1911 to 1919. Hupp worked for Ford and Oldsmobile prior to founding Hupmobile with his brother, Louis. After disagreements with the company’s financial backers, Robert left the business in 1910 to start the RCH Company, later changed to Hupp-Yeats Electric. Hupp-Yeats automobiles had stylish sloping hoods, curved roofs, and underslung bodies, and were available as coupes or runabouts. In 1911, they were priced from $1,650 to $2,150 and delivered as much as 125 miles on a charge. The brand most closely associated with Detroit and electric cars is Detroit Electric, for many more reasons than the name. The firm was originally named the Anderson Carriage Company, and moved from Port Huron to Detroit in 1895 in order to take advantage of the larger market. Anderson’s was a big carriage works, making everything from inexpensive utility wagons to beautiful opera coaches. The company put out its first automobile, the Detroit Electric Model A, in 1907. That year, it sold only 10 cars. In 1908, its first full year of manufacture, the public purchased 184 of its four models—a very respectable number, given the regional nature of business at the time and the still-small luxury automobile market. By 1910, Detroit Electric had become the best-selling brand of electrics in the country, delivering 797 automobiles and a small number of electric trucks. In the early 1910s, Detroit Electrics were priced at $2,000 for an underslung roadster to as much as $4,750 for a limousine with the Edison nickel-steel battery. (It’s worth noting that, during this time period, the average annual income was about $1,000.) Detroit Electric wasn’t a particularly innovative company. But William C. Anderson and his team, which included chief engineer George Bacon, had great business sense and understood their clientele very well. For rich women, Anderson’s team focused on luxury. Each of the Detroit Electric coupes and broughams came with a flower vase, a case for makeup and business cards with a built-in watch, and in some cases a “gentleman’s smoking kit.” The upholstery choices included “22 ounce superfine Waterloo broadcloth or leather, blue, green, or maroon shades. Imported goatskin, fancy novelty cloth or whipcord on order.” Standard exterior paint colors were blue, Brewster green, or maroon, although they would paint a car any color a customer chose for an additional fee. (In 1909, a Mr. Capewell bought Detroit Electric’s first stretch limousine in an eye-popping shade of canary yellow.) As new features came onto the market from other manufacturers, the management team at Anderson would evaluate them and incorporate the ones that made sense for their customers. Examples include emulating the direct-shaft drive of Baker electric cars—which ensured a quieter ride—as well as a “duplex drive” feature, which allowed the driver to sit either in the front seat or the back seat. (The Ohio Electric Car Company had introduced this idea a year before Detroit Electric.) Interestingly, enclosed automobiles of the day were designed much the same as the coaches that preceded them. Typically, a bench seat was fitted against the back wall of the automobile, allowing for two passengers to sit comfortably. In front of them was either another bench seat set against the front wall facing back, or a combination of a small bench seat set into the front left corner of the interior, facing diagonally toward the rear, and a flip-up “jump seat” on the right side, also facing back. The driver would sit in the left rear and have to look around passengers to see the road. This feature, nonsensical as it may seem, was the way horse-drawn coaches were designed, and it was what the luxury market expected. But as the streets became more crowded, accidents occurred on a more frequent basis. This forced municipalities to enact ordinances banning the use of rear-drive automobiles. The “Detroit Duplex Drive” feature allowed for the traditional layout with rear drive, but the left front seat also could be turned to the front to allow the driver to navigate from there. Detroit Electrics, like most enclosed cars of the day, used steering “tillers,” rather than steering wheels. The tiller could be placed against the side of the interior when not in use and was swung up by the driver when he or she was ready to go. Detroit Electric purchasers included Thomas Edison, Pierre DuPont, David Gamble, C.W. Post, Mrs. J.D. Rockefeller Jr., Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, Anna Kresge, Charles Steinmetz, Stanford White, and the Steinway family. Surprisingly, they were joined by the owners of several gasoline-automobile companies of the day, including Henry Ford—who bought two for his wife and one for his son—and the men who oversaw Packard, Stutz, Cadillac, E-M-F, Studebaker, and General Motors. It should be noted that the Ford Motor Company took a hard look at electrics, going as far as developing a number of designs in 1914. During this period, Henry Ford’s friend, Thomas Edison, had experienced some serious financial problems, and Ford thought he would help him by building cars that used the inventor’s batteries. Unfortunately, Ford’s designers were unable to create a car that fit within their boss’ pricing parameters—namely, they couldn’t build one nearly cheaply enough. Drawbacks The cost of electric cars, even at the low end, wasn’t the only thing holding most people back from making a purchase. Range was a concern, particularly as most rural areas were not yet wired for electricity. It was easy to transport gasoline out into the country, less so electricity, so drivers of electrics—for the most part—had to stay close to home. Compounding the problem, the batteries needed half a day to charge, so there was no short stop to “refuel” before getting on the road again. The biggest problem, however, was the electric car’s identification with women. In the early 1900s, “manliness” wasn’t something most men would compromise, so the idea of driving a “woman’s car” was unthinkable. The electric car manufacturers tried to entice men with low-slung, racy-looking roadsters, but were unsuccessful at breaking out of the stereotype. Ultimately, the self-starter developed by Charles Kettering in 1911 spelled the end of the early electric. Kettering’s starter allowed drivers of gasoline automobiles to start their cars without a crank, which made them acceptable to most female drivers. The Fall With all of these factors working against the electrics, the market for such cars continued to shrink until the late 1910s, by which time most manufacturers had gone under. Detroit Electric, however, remained in business until 1939, but not without some effort. At its high point, the company manufactured almost 2,000 vehicles a year. Through the 1920s, its annual output dropped to the low hundreds. Then, the stock market crash of 1929 put it into bankruptcy. Its assets were purchased and the new company struggled along for another decade, manufacturing a handful of cars each year from a combination of new and old parts and staying in business only because of the service work they performed. By 1939, there wasn’t enough of that to keep the company afloat, and it quietly folded. All told, Detroit Electric built nearly 14,000 electric vehicles—the most of any U.S. manufacturer. In the wake of the demise of the early electric, one can’t help but wonder how Flanders Electric might have reconsidered this statement from their 1912 sales brochure: “Is there a rule to guide one? There is. And it is a very simple one. If an innovation is logical it will survive. It will become permanent. On the other hand—if it is one of those so called improvements devised by [hare]-brained designers simply to create a selling argument or a talking point; if, in short, it is but the hobby of an individual it will become a fad of the moment and as fads do will soon pass into oblivion.” D.E. Johnson is the award-winning author of the Will Anderson Historical Detroit mystery series. Those books include The Detroit Electric Scheme, Motor City Shakedown, Detroit Breakdown, and Detroit Shuffle. Thanks to the Motor Cities National Heritage Area for their assistance with this story. SIDEBAR: A GLOSSARY OF EARLY CAR BODY TERMS In 1916, the Nomenclature Division of the Society of Automobile Engineers established formal definitions for the many styles of car bodies then on the road. Among the entries listed were: Roadster— An open-body automobile seating two or three persons. It may have additional seats on the running boards or in a tonneau (rumble seat). Runabout—Editor’s note: This is often a synonym for “roadster.” Touring Car—An open car seating four or more with direct entrance to the tonneau. Coupe—An enclosed automobile seating two or three. Sedan—A closed car seating four or more all in one compartment. Limousine—A closed automobile seating three to five inside, with the driver’s seat outside, covered with a roof. Brougham—A limousine seating three to five with no roof over the driver’s seat. Source: The New York Times, August 20, 1916.  I had a wild morning today--something I never thought would happen. Henry Rollins (yes, that Henry Rollins) interviewed me for his History Channel show, 10 Things you don't know about (subject). This episode is on Edison, Tesla, and the War of the Currents, and it ought to be fascinating (for many more reasons than me being on it). The show will air Fall 2014, exact date TBD. But set your DVRs for all the episodes of this show. It promises to be very interesting!  Scott Hunter froom Asylum Entertainment asked me a few weeks back if I would be interested in appearing on this program, and asked if I knew anyone with an electric car that might have had Edison's nickel-iron batteries. I immediately thought of my pal Jack Beatty, seen here with Henry. Jack has helped me out with some of my events in the past and owns two of the maybe eighty running vintage Detroit Electrics in the U.S.  Jack is a real gentleman and was also tickled at the idea of being on a History Channel program, so no persuasion was needed. They set us up for today at 8:00 AM. It's an almost two-hour drive to Jack's place for me, so I hit the road a little before I woke up. Fortunately, I didn't kill anyone. Henry interviewed me on camera for about an hour, and then they went on to the cars with Jack.  While they were getting ready to film, Henry and I chatted about music and hi fi. He's an audiophile with six stereos in his house, including what has to be one of the best sounding systems anywhere - Wilson speakers, VTL amp and preamp, etc. He is a music fanatic and when he talks about recorded music, he means music on vinyl. No MP3s for this man! He's coming back to Michigan for a spoken word concert in October and said he'd hook me up on his guest list. Pretty sweet. It's amazing what opportunities come along when you're not paying attention! The following essay appears in the Fall 2013 issue of Mystery Readers Journal.

When I began researching early Twentieth Century Detroit for my historical mystery series, I came across all kinds of information about electric cars. I had some vague notion that electrics existed back in the day, but I really had no idea how significant a part they played in automotive history. At the turn of the Twentieth Century, there were almost twice as many electrics on the road as there were gasoline cars, but twenty years later, the quieter, cleaner-running vehicles had all but disappeared. The electric car was a superior design, simpler and more reliable. Yet during an age when gasoline-powered vehicles broke down so often they came from the factory with a repair kit, electrics were wiped out. That smelled like a conspiracy. After watching Who Killed the Electric Car?, my mind filled with possibilities. As an unpublished author, I needed a conspiracy. At the top of my wish list—a cabal led by Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller conspiring to wipe out electrics. Imagine a conference room at the Standard Oil Company, with Ford and Rockefeller and their henchmen. Rockefeller closes the blinds, strolls to the head of the table, and says, “Gentlemen, we have a problem.” Then, though a series of shady business dealings, they work behind the scenes, manipulating the industry like a pair of puppet masters, probably ordering the murders of a few men along the way, until they squeeze the electric car companies (the good guys) out of business. For the book, I’d need a hero—some dashing electric car whiz kid who’s out to save the world, until he’s crushed by the nefarious forces of evil, led by Big Oil. Can you say “bestseller?” I started digging in with Henry Ford. It wasn’t until late 1908 that he hit on his first successful vehicle—the Model T. Prior to that, he had little to gain with the death of the electric. Okay, so how about later? Turns out Ford wasn’t against his company producing electrics. He and Thomas Edison, who were close friends, discussed the possibility of Ford Motor Company manufacturing electric cars on numerous occasions, but Ford’s engineers were never able to design one they could build cheaply enough for his taste. Further, while Ford had his share of faults (and a few other people’s shares as well), he was a loyal friend. Edison was building batteries for electrics, and it’s hard to imagine Ford cutting him off at the knees like that. I kept digging, but I wasn’t able to come up with any evidence of Ford’s involvement in the conspiracy. So on to Rockefeller and Standard Oil. Talk about a guy with a motive—in the early 1900s he controlled more than 90% of the United States’ oil production and only a little lower percentage of the sales of refined oil products. He had a lot to lose if electrics supplanted gasoline-powered cars. So what did he do? Nothing. Damn it. I could see that number one spot on the New York Times list going up in smoke. Still, I wanted to know. Was it the pope? That would work. How about Teddy Roosevelt? Not quite as sexy, but still good. Andrew Carnegie? J.P. Morgan? Nope. It was me. And you. The consumer killed the early electric. Aided by Charles Kettering. Early electric cars were expensive. The cost of batteries, the technology of which has changed little to this day, was extremely high, putting the price of electrics at a serious premium to gasoline-powered cars. The good news was that automobile owners were rich, because most gasoline cars cost about two year’s wages for the average worker, and most electrics were 50% higher than that. The folks who bought these things were the upper-class, and they could afford any car they wanted. So, if the manufacturers of electrics stuck to the high end, they would have been okay, right? Well, no. There were other problems, such as charging. First of all, you had to be somewhere that had an electric grid, not a given in the early Twentieth Century. Next, you had to leave your car all night to charge it. No quick stop at the gas station and off you go! Range complicated the problem. Most of the early electrics were rated at around fifty miles per charge. That was enough for most uses, but not all, and very few people owned more than one car. By the 1910s, the range of electrics had doubled to 100 miles or more per charge, but still; after 100 miles—if you dared try to take it that far—you were stuck for eight hours or so while your batteries charged. And again, that’s assuming you were somewhere that had electricity. So, electric cars were expensive, took a long time to charge, and had limited range. Sound familiar? But they had one thing going for them—women dug electrics. Why? Because of the reasons you might think: they were quiet and didn’t spew noxious fumes. There was a bigger reason, though. They could be started with the flip of a switch. To start a gasoline-powered car, you had to bend down in front of it, grab hold of the crank, and give it a spin. Talk about unladylike. Woman drivers at this point in history were already progressive, really on the cusp of impropriety. To perform a task such as starting a gas car was unthinkable. The electric car manufacturers focused on their primary demographic—rich women. By doing so, they made electrics de facto women’s cars. It’s not like the men of the early Twentieth Century cornered the market on machismo—men have always wanted to be “manly,” but this was the period in which Teddy Roosevelt’s “Strenuous Life” was the model. Men were men, and by George, they weren’t going to be driving a woman’s automobile. Then, in 1911, Charles Kettering went and designed a self-starter for gasoline cars that allowed drivers to start them by flipping a switch. That was the beginning of the end. Women began choosing their automobiles for reasons other than how they started, and a much wider array of gasoline-powered vehicles offered many tempting choices. By the time World War One wrapped up, electrics were all but gone from the American landscape. Only a few electric car manufacturers survived into the Twenties, and only one that I’ve found (Detroit Electric) made it past the Great Depression, and they scraped along by the skin of their collective teeth until 1939, when they finally gave up. Conspiracy? Unfortunately, no.… Sigh. Bye bye NYT #1. It wasn’t Ford or Rockefeller or Roosevelt or Carnegie or Morgan. Or even Kettering. As the great philosopher Pogo so famously said, “We have met the enemy … and he is us.” Award-winning author D.E. Johnson has published four novels in his Historical Detroit mystery series: The Detroit Electric Scheme, Motor City Shakedown, Detroit Breakdown, and Detroit Shuffle. His interest in the automobile industry is genetic—his grandfather was the Vice President of Checker Motors. Johnson is currently working on a crime novel set in early 1900s Chicago that has absolutely nothing to do with the auto industry. Killed in the press  The Detroit Electric Machining Room circa 1910 I had no idea how often something like the scene at the beginning of The Detroit Electric Scheme happened in real life. (Not the murder part, just the press "accident" part). Two men at one talk this winter told me about their experiences, one at a Chrysler plant, the other at a Buick plant. One of the men had to clean out the press after a repairman had been working on the press from the inside and it stamped him. He was completely pulverized. Nothing left but liquids. The other knew a machine operator who had been leaning inside the press and put his hands up on the side of it to lever himself out. His head was still inside when one of his hands hit the switch. Last night at the Cromaine Public Library, one of the men in attendance said he used to work at Fisher Body, and he told me about the evolution of these press accidents and the attempted solutions by management. He had to clean up after one man was crushed in a press and paid close attention to it from then on. Initially there was one man at the control (single switch) while four other men would put the metal in the press, align it, and remove it when it had been stamped. When the man at the switch got distracted or hit the button accidentally , any of the four could lose a hand, arm, or head, depending on what they had in the machine at the time. They went to a two switch system, so the button couldn't be pushed accidentally, but they still had the problem with the distracted operator. Also, machine operators for whom pushing two buttons was too much effort would push in one button and wedge it in place with a toothpick, so he'd just have to push one button to start the press. Additionally, men were losing legs because they would put their leg up to stretch at just the wrong time. Next came all four men having to stand on certain spots or all hold onto a bar outside the press in order for it to work. In the meantime, hundreds (thousands?) of men were maimed or killed by these machines. Think of the outcry today if something like that was happening (in this country. I'm sure there are similar problems in sweatshops around the world, but we don't hear about those.) Life was cheap in the U.S. in those days, particularly when the men were easily replaceable and there wouldn't be publicity problems for the company. It was just the cost of doing business. Of course, the families of those men wouldn't feel the same way. Batteries & Cost

In 1911 you could order a Detroit Electric with Thomas Edison's new nickel-steel batteries. Edison had been promising his new batteries for a decade and unsuccessfully tried to manufacture them numerous times before, but by 1910 he finally had them ready to go. For electric car manufacturers, this was the moment they'd been waiting for. The average mileage on a charge would go from 50 to 100! With the roads being what they were at the time, 100 miles would take you just about anywhere you wanted to go. In fact, Detroit Electric ran a mileage test in the fall of 1910 with Edison batteries and set a mileage record of 211.3 miles on a single charge. (Chronicled in The Detroit Electric Scheme.) And then Baker Electric one-upped them in December with over 243 miles! A 1911 Detroit Electric cost between $2,000 and $3,500, depending on the model. The Edison battery added $600 to the cost. Ouch. As a contrast, a Model T roadster cost $600 for the whole car! Of course, it was nothing - at all - like a Detroit Electric. Still, the average cost of a new car in 1911 was $1,130. Unfortunately, batteries, whether nickel-steel or lead-acid, didn't get significantly cheaper. Gasoline automobile prices kept diving, driven by intense competition and improvements in manufacturing efficiency. The electric car companies never gained that advantage, and their prices stayed very static. The price gap kept growing, and the self-starter for the gas cars eliminated the greatest advantage the electrics held--easy starting. By the time "The Great War" began, electrics were on the ropes. By 1920 they were all but gone. (Although, believe it or not, Detroit Electric was in business into the 1940's!) Who Killed the Electric Car (Part 2)

The "Self-Starter" In the early years, electrics had a very significant advantage over gasoline and stem-powered cars - they were easy to start. All you had to do was flip a switch, and, assuming the batteries were charged, the car was ready to go. With a steam car, you had to stoke up the boiler and wait for the better part of an hour before you could get going. Not exactly convenient. Add to that the possibility of the boiler exploding if you weren't an expert, and it was pretty clear that this method of combustion was not going to be long-lived in automobiles. Gasoline cars were easier and more convenient to start than that, but you still had to get your spark and throttle controls set just right and then crank the engine started. For all but the most adventurous women of the day, it was unthinkable to engage in such unladylike behavior. For men, it was all part of the adventure of the automobile, but it was still a pain - sometimes literally. People were injured, maimed, and even killed by the crank spinning back on them. In fact, this is what inspired the invention of the first reliable self-starter for a gasoline automobile. Byron Carter, the founder of the Carter-Car Company, stopped to help a woman whose car had stalled. He didn't check the spark before he tried to start it. The engine backfired, and the crank spun back, breaking his arm and smashing his face and jaw. He died of gangrene a few weeks later. His friend, Henry Leland, at the time the owner of Cadillac, vowed to develop a self-starter for a gasoline automobile that really worked. Self-starters had been around for a while - they just didn't work well or often. So Leland brought in Charles Kettering, the inventor of the electric cash register and an electricity generator known as the "Delco" (a sign of things to come for Kettering). Kettering introduced his self-starter in early 1911, It was first used in the 1912 Cadillacs to great reviews, and went on to sweep the industry. The advantage in easy starting that the electric had over the "infernal combustion" vehicle was gone, and with it a significant percentage of the electric business. Who killed the Electric Car?

Electric cars were more popular at the turn of the 20th Century than gasoline cars, but by 1920 they had almost entirely disappeared. Was this due to a conspiracy between Henry Ford and Standard Oil's John D. Rockefeller? I wish. Sexy conspiracy theories are always more exciting than the truth. I find it interesting that most of the issues that dogged electrics a hundred years ago are the same problems they have today. Hoping that someone else finds it interesting as well, I will post a series of entries on the reason the electric car died. First . . . The American Man and the Art of Touring The automobile opened up this country for exploration. Previously, if a person wanted to travel they would either hook up the horse and wagon or take a train. They could direct the horses wherever they wanted and weren't limited by a schedule, but horses couldn't cover a lot of ground in a day. A train traveled faster and further, but they were limited by the tracks and the train's schedule. With an automobile a traveler could cover a lot of ground and go wherever they wanted, whenever they wanted. And the automobile was so doggone manly. With his scarf trailing behind him in the breeze, his goggles fixed firmly in place, and the woman he was courting on the seat next to him, a man could travel the countryside. If he was lucky, he could stop in a secluded area for a picnic and perhaps a bit of romance. Cars were an accessory to a "manly man." The cooler the car, the cooler the man (or so the men thought. Sound familiar?) Cars were also expensive. Few people could afford one until the 1920's. In the early part of the 20th century, owning a car signaled to all that you were wealthy. Touring became the rage, the pastime for the rich. It was the primary reason most men bought cars. This was a problem for the electric. Steam-powered automobiles ran on water, so the boiler could be filled practically anywhere. Gasoline-powered cars could be driven anywhere gas could be delivered, which, as the internal combustion engine grew in popularity for things like tractors, was virtually anywhere. Charging an electric required electricity--something not readily available in the country. Well into the 20th century, most rural areas didn't have electrical service. Those that did most often didn't have a facility designed to charge an electric car. If a man took his electric out for a tour, he might not get back. In the early 1900's electrics got an average of about fifty miles on a charge. Who wanted to take the chance of getting stranded? So if electrics were the third choice for touring, who bought them? Mostly city folk, who drove only in the city. There were a few dandies who didn't mind being seen behind the wheel of an electric car, but they were purchased most often to be driven by women. And the vast majority of women didn't--and wouldn't--drive. The second most common customers were city doctors--house calls, you know. Starting quickly and easily was important in a life or death situation. Electric delivery trucks were also a fairly common purchase during this time, for things like coal, ice, and milk--products that were delivered within a relatively small geographic area. The purchase of purely electric cars was limited to a tiny part of the population: people who could afford to buy a car just for city driving. (And remember, this was before the rise of the middle class.) Given that few men bought cars to drive around a city, this was strike one against the electric. Next time--Battery Technology and Cost |

AuthorD.E. Johnson: Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed